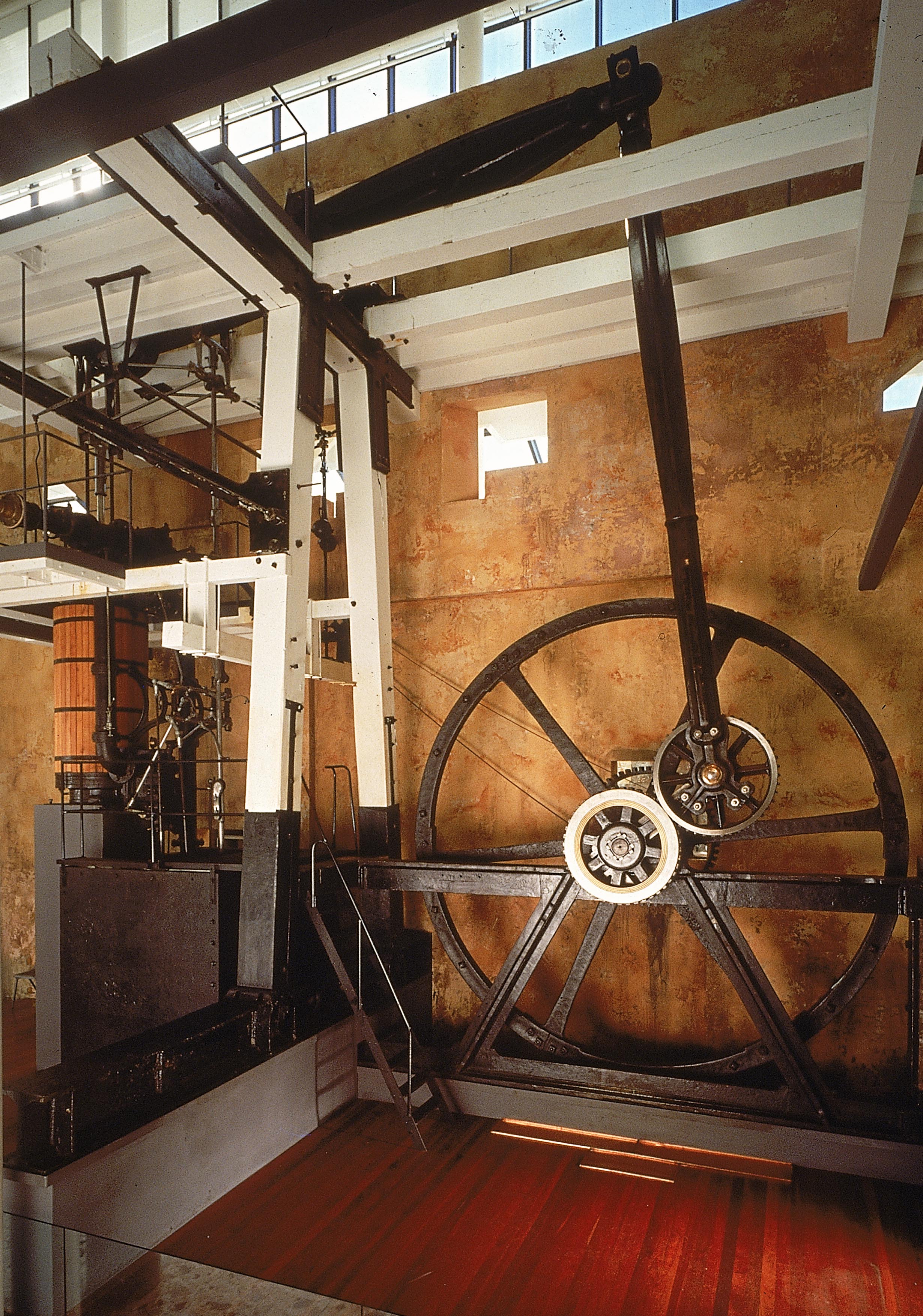

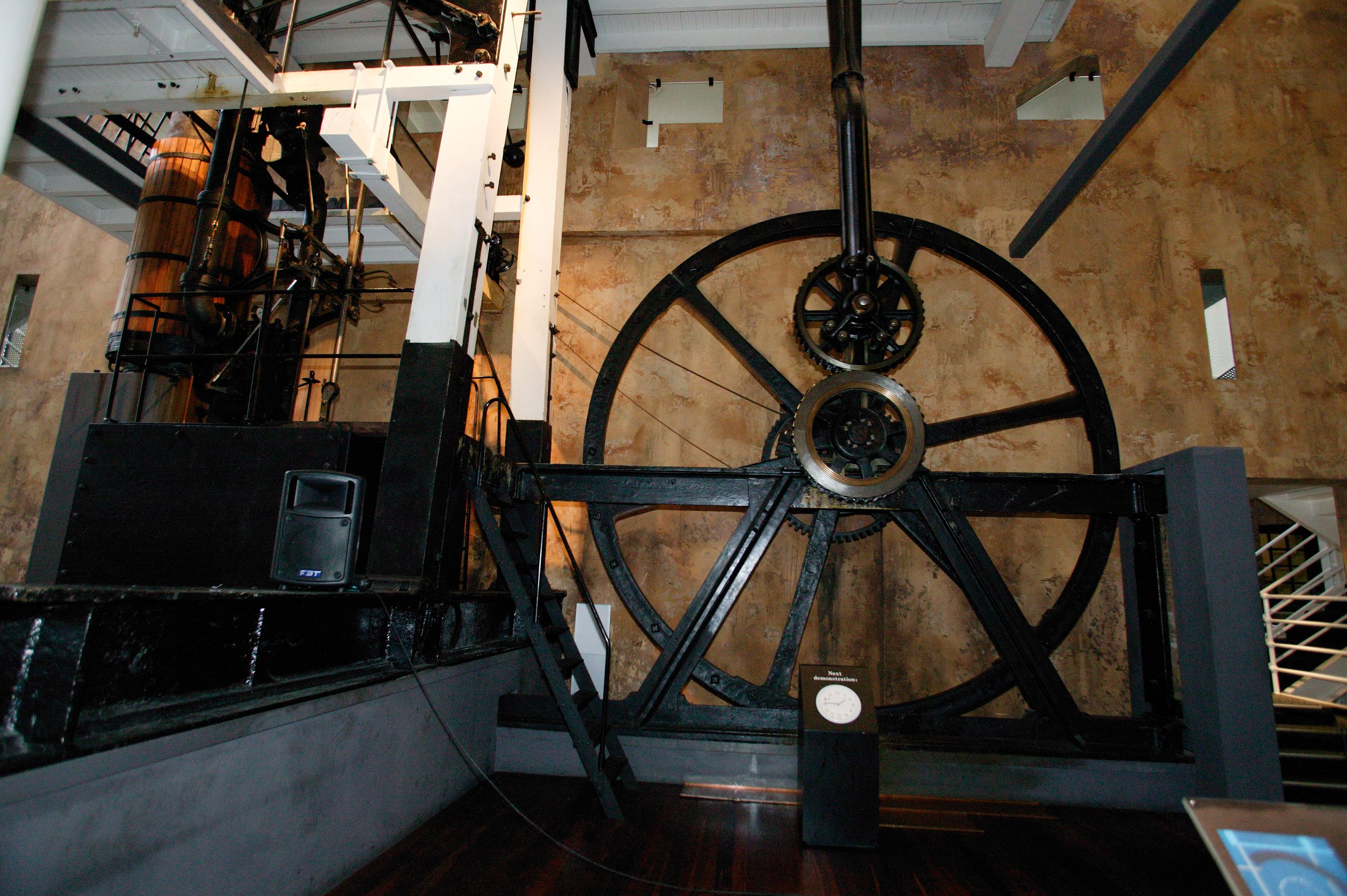

Boulton and Watt rotative steam engine, 1785

Object No. 18432

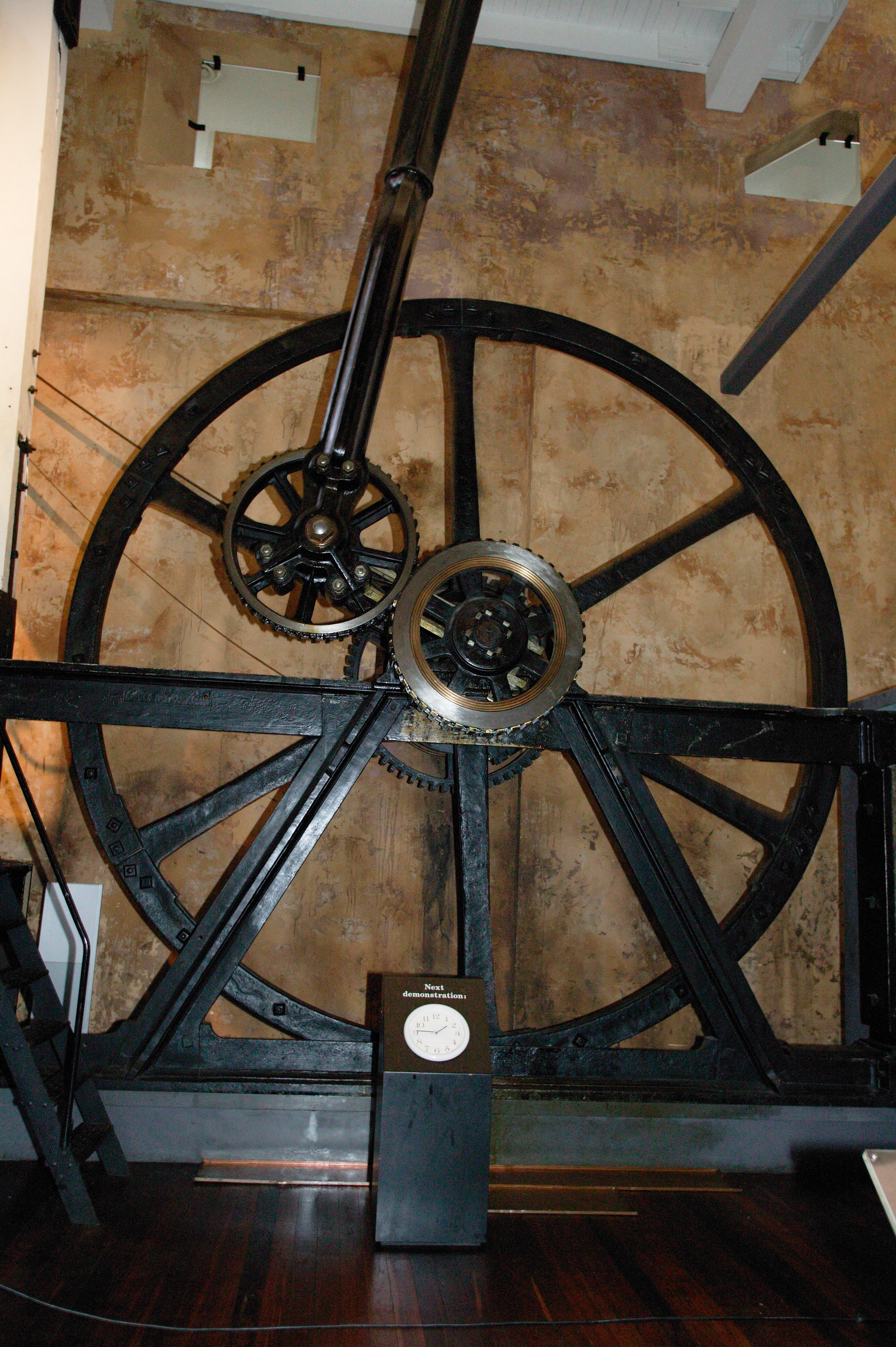

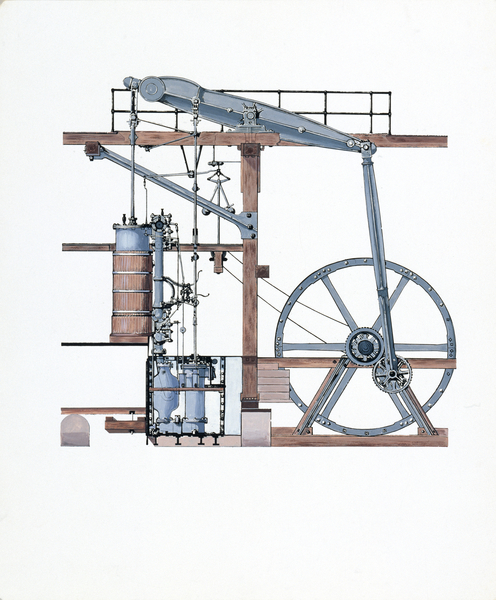

This is the oldest rotative steam engine in the world. It embodies the four innovations that, together with extended patent protection, Matthew Boulton's capital and entrepreneurship, and James Watt's engineering skill and prudent management, made Boulton and Watt rotative engines the first commercially successful stationary power plants that were independent of wind, water and muscle. Thomas Newcomen made the first successful steam engines in the early 1700s in England. Their output was reciprocating motion, and they were used mainly for pumping water out of mines. A few powered mills and factories indirectly by pumping water from below a water wheel to above it for re-use. James Watt's first and most significant innovation was the separate condenser. On each stroke of a Newcomen engine, the cylinder was heated (by steam) and cooled (by a jet of cold water that cooled the steam so that it condensed to water) to create a vacuum so that the atmosphere pushed the piston down. Watt decided to do the condensing in a separate vessel, ensuring that the cylinder remained hot. The separate condenser greatly increased efficiency and thus improved economy. Watt invented the parallel motion mechanism, which (by replacing a chain) allowed the piston to push the beam up as well as pulling it down. By ensuring the piston rod was constrained to almost truly vertical movement, it allowed the cylinder to be sealed at the top. Thus it enabled power to be doubled without increasing cylinder size. Boulton and Watt introduced the centrifugal governor to control engine speed. Adapted from mill practice, it was the first feedback device designed for use with engines. The firm's fourth innovation, sun and planet gearing, was devised after a competitor patented the use of the crank in steam engines, the crank being a simpler mechanism for converting reciprocating to rotative motion. Boulton and Watt could have chosen to share the crucial separate condenser patent with that competitor in return for the right to use the crank; the sun and planet allowed them to maintain their position of never granting licences. As Boulton and Watt engines were prime movers in the Industrial Revolution, this very significant engine represents not just invention and entrepreneurship, but also wealth creation, mass consumerism, great changes in working life, a massive shift in the use of resources, and consequent damage to the natural environment. Debbie Rudder, curator, March 2007 On 29 May 2009, the Governor of the Bank of England announced that an image of the Whitbread engine will feature, along with portraits of Boulton and Watt and an image of Boulton's Soho Manufactory, on a fifty pound banknote planned for release in 2010. The selection of our engine for this banknote recognises its significance in both engineering and economic history. (The banknote was released on 2 November 2011, and the Museum's copy is object 2012/6/1.) Reference http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/news/2009/043.htm Debbie Rudder, curator, June 2009

Loading...

Summary

Object Statement

Steam engine, double-acting beam type, cast iron / wrought iron, made by Boulton and Watt, Birmingham, England, 1785, used at Whitbread's Brewery, London, England, 1785-1887

Physical Description

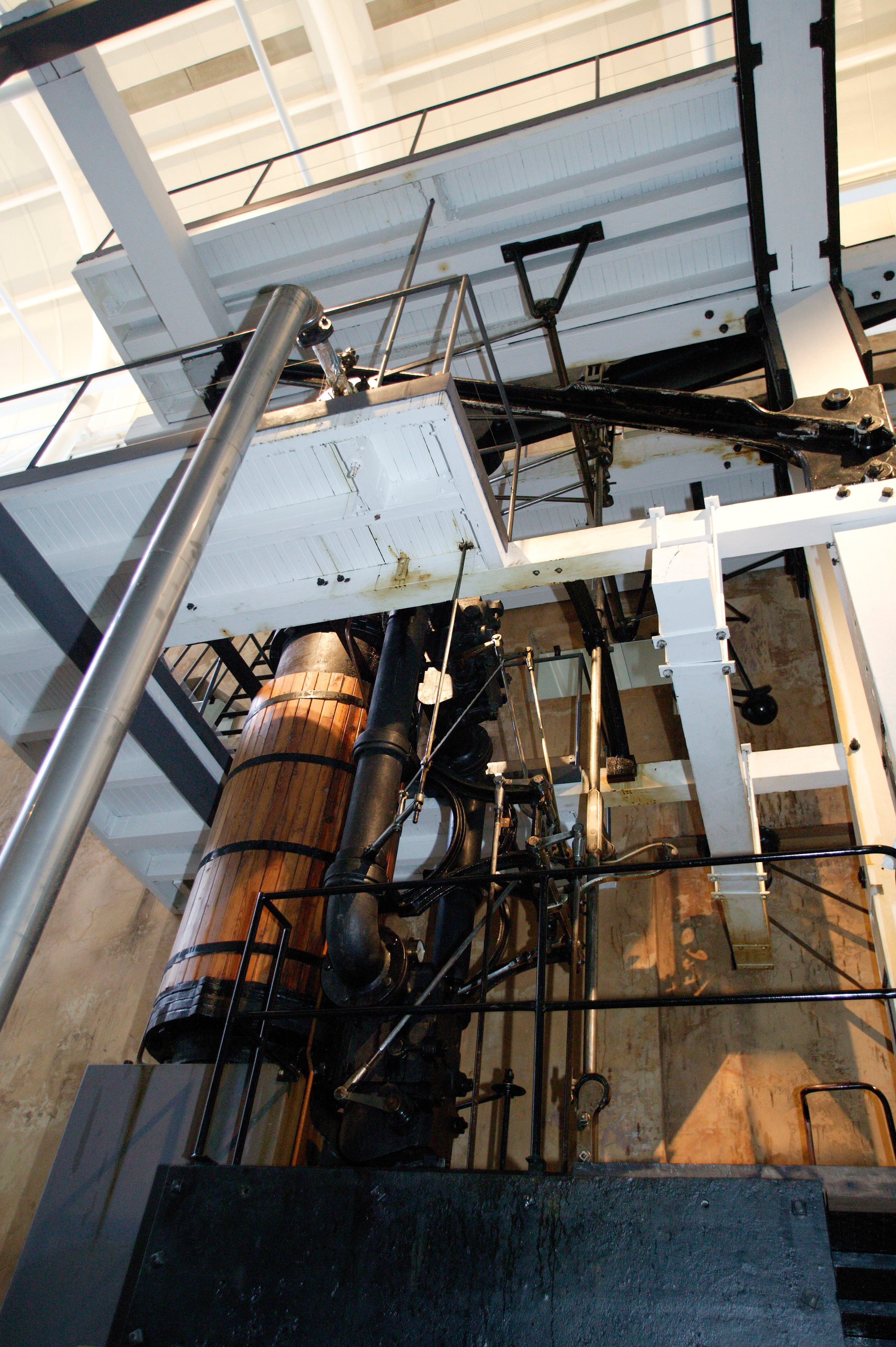

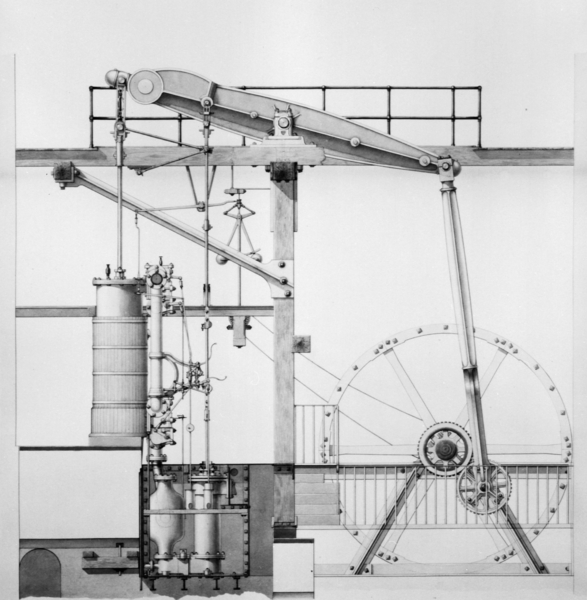

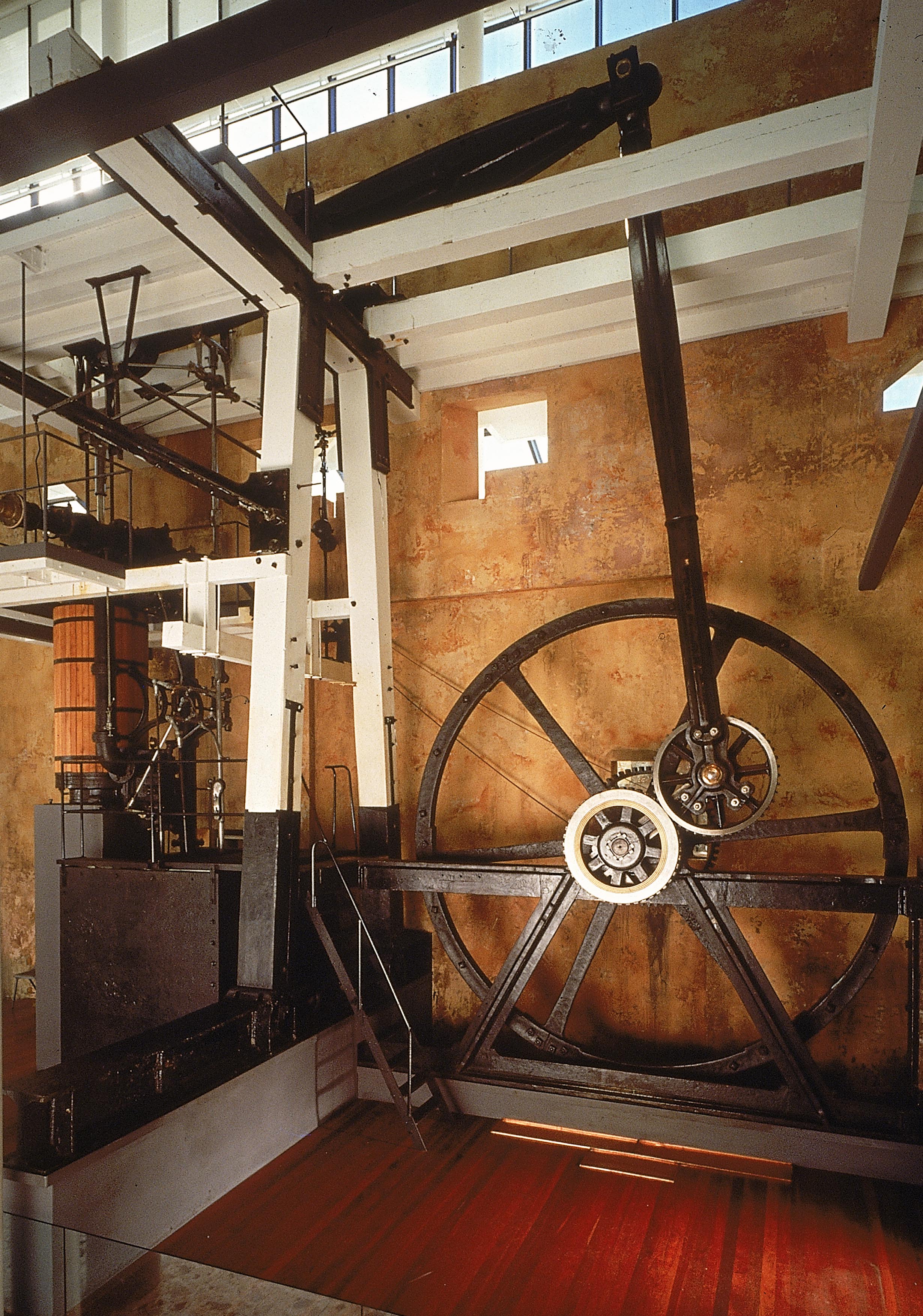

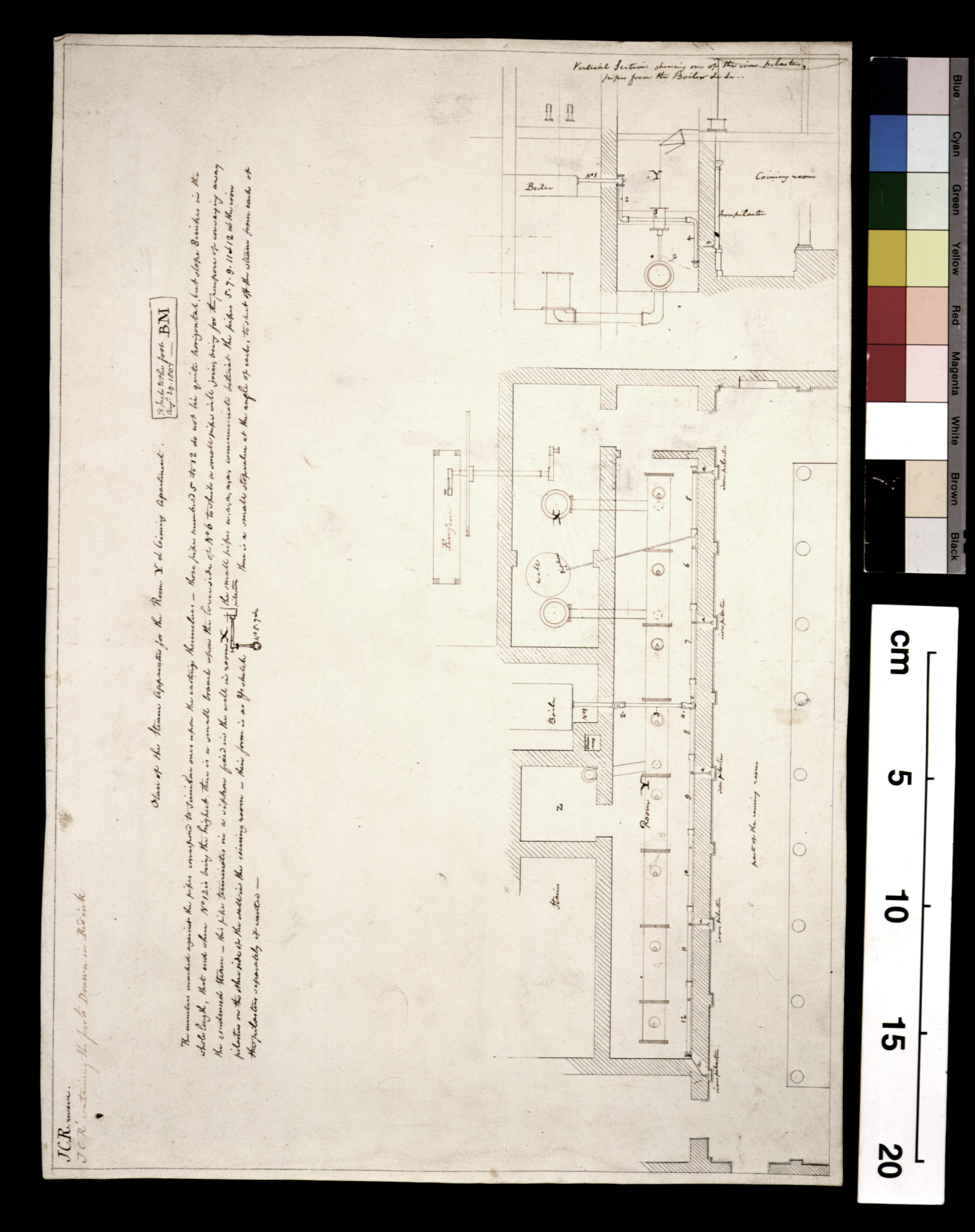

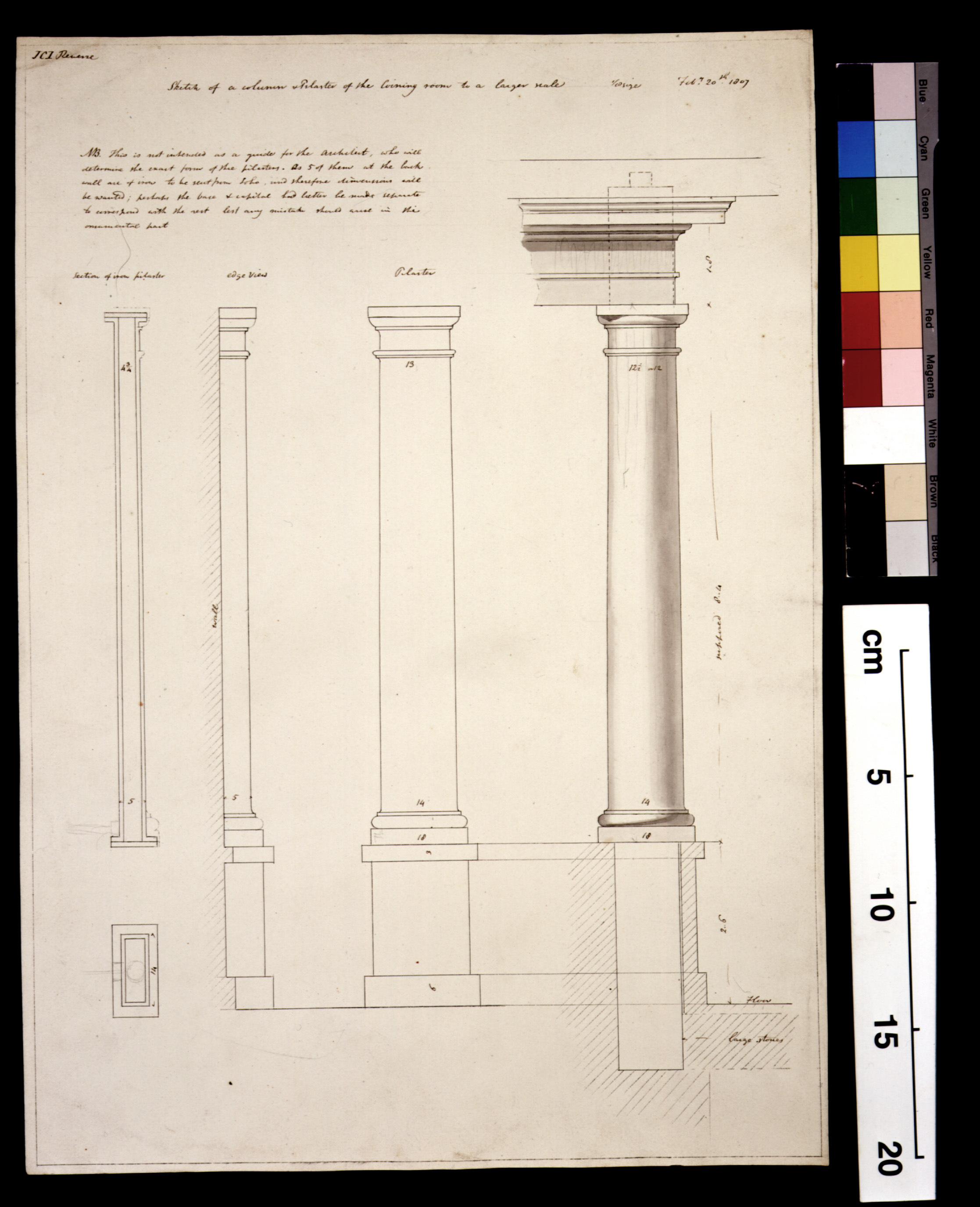

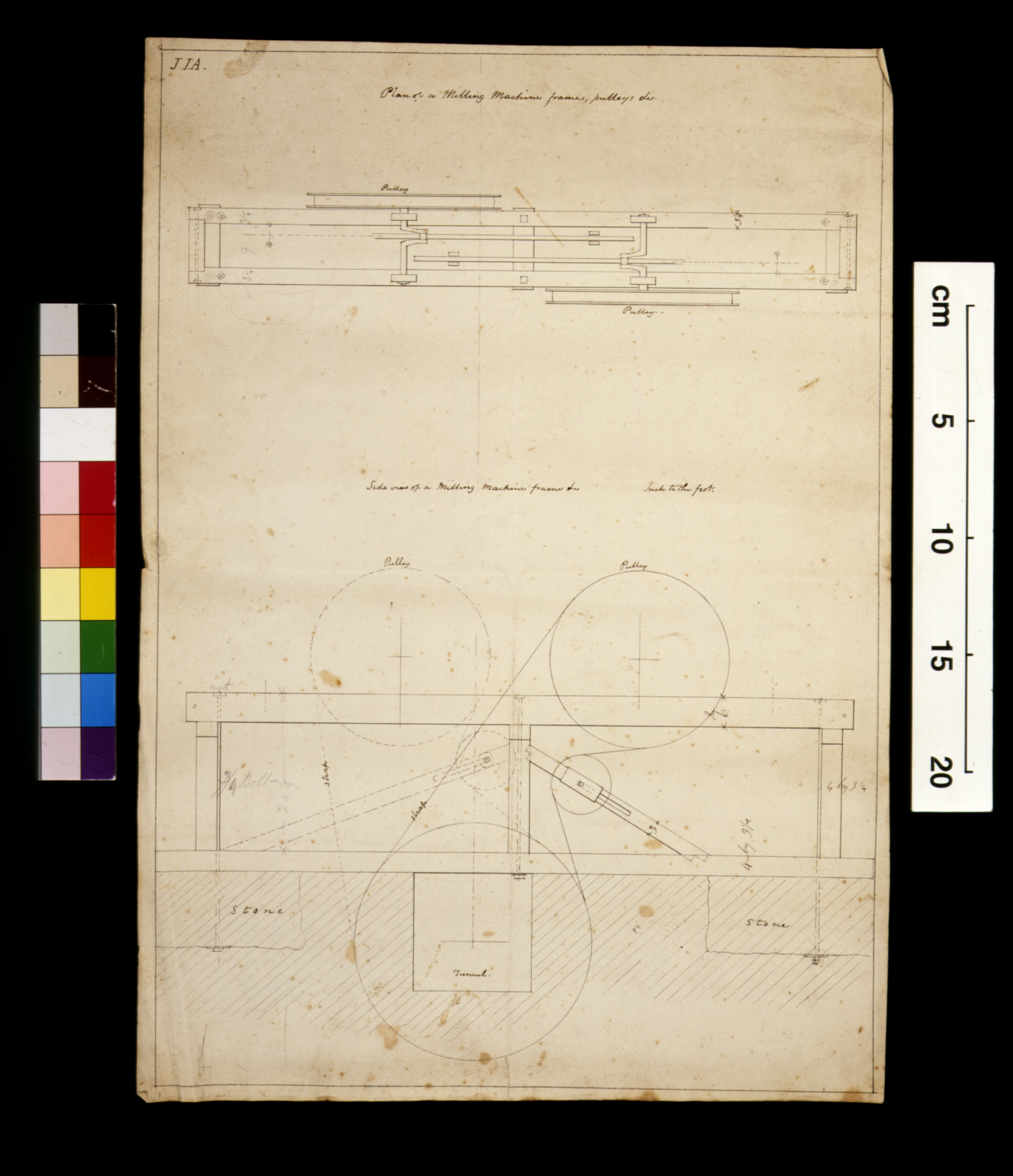

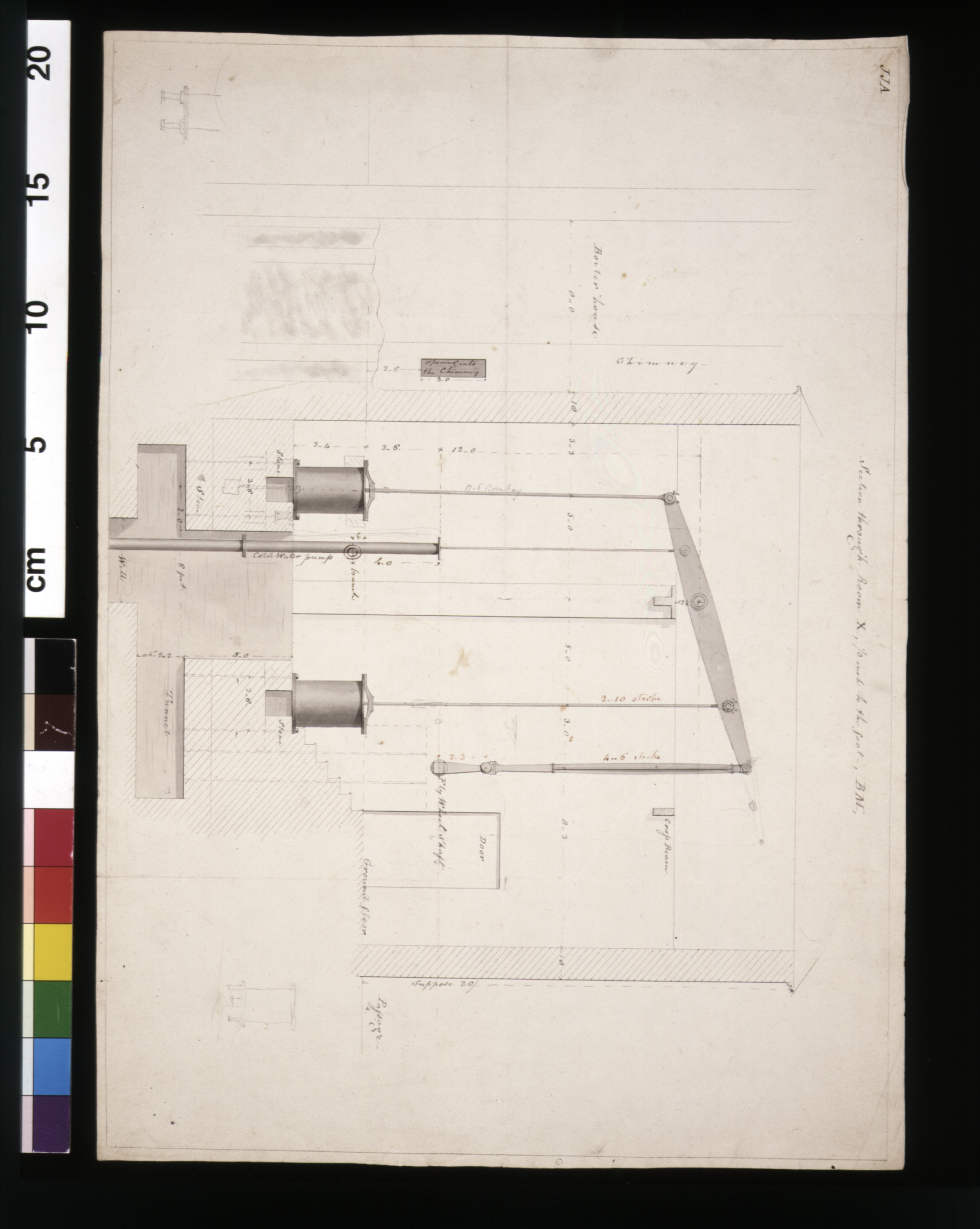

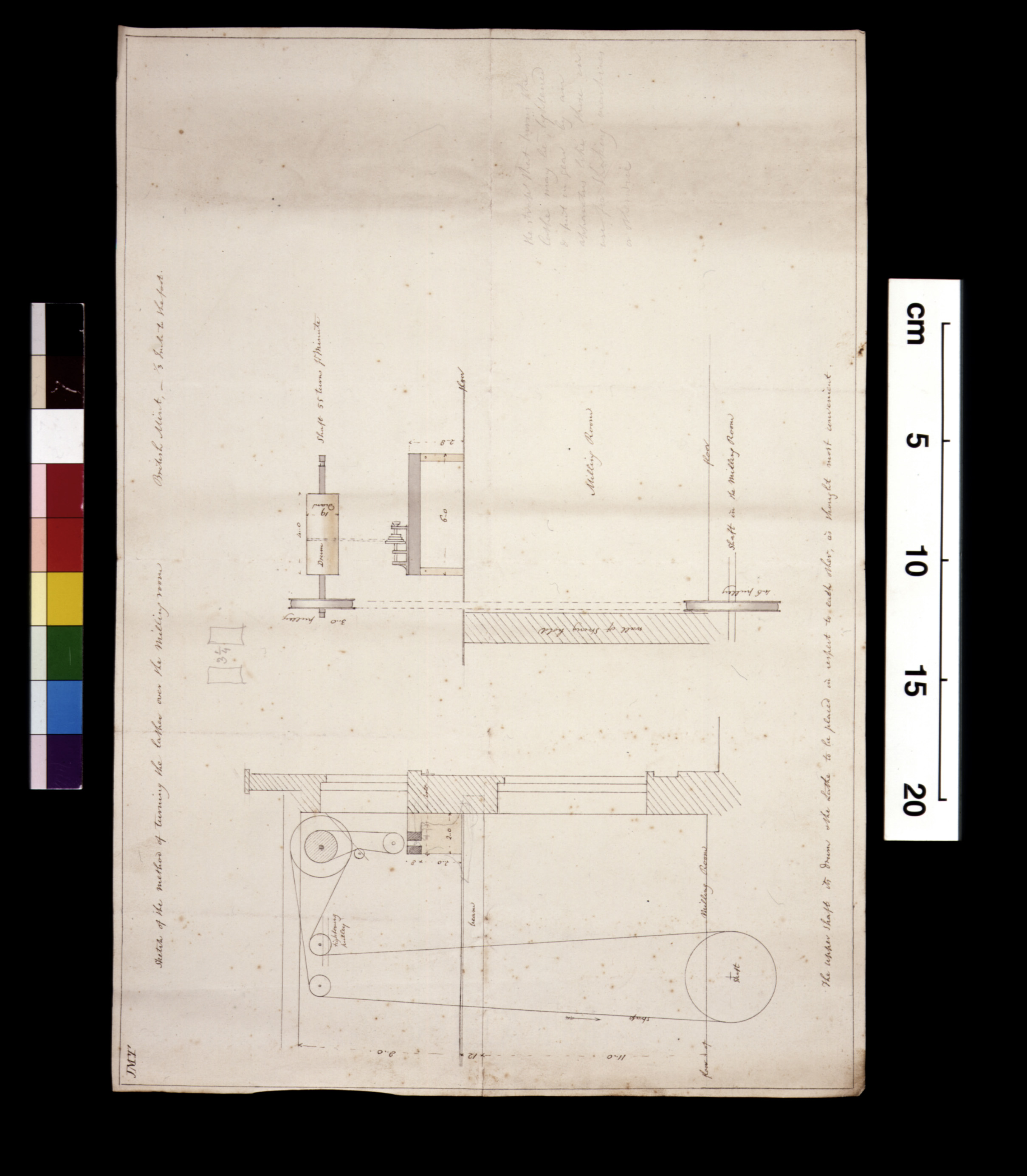

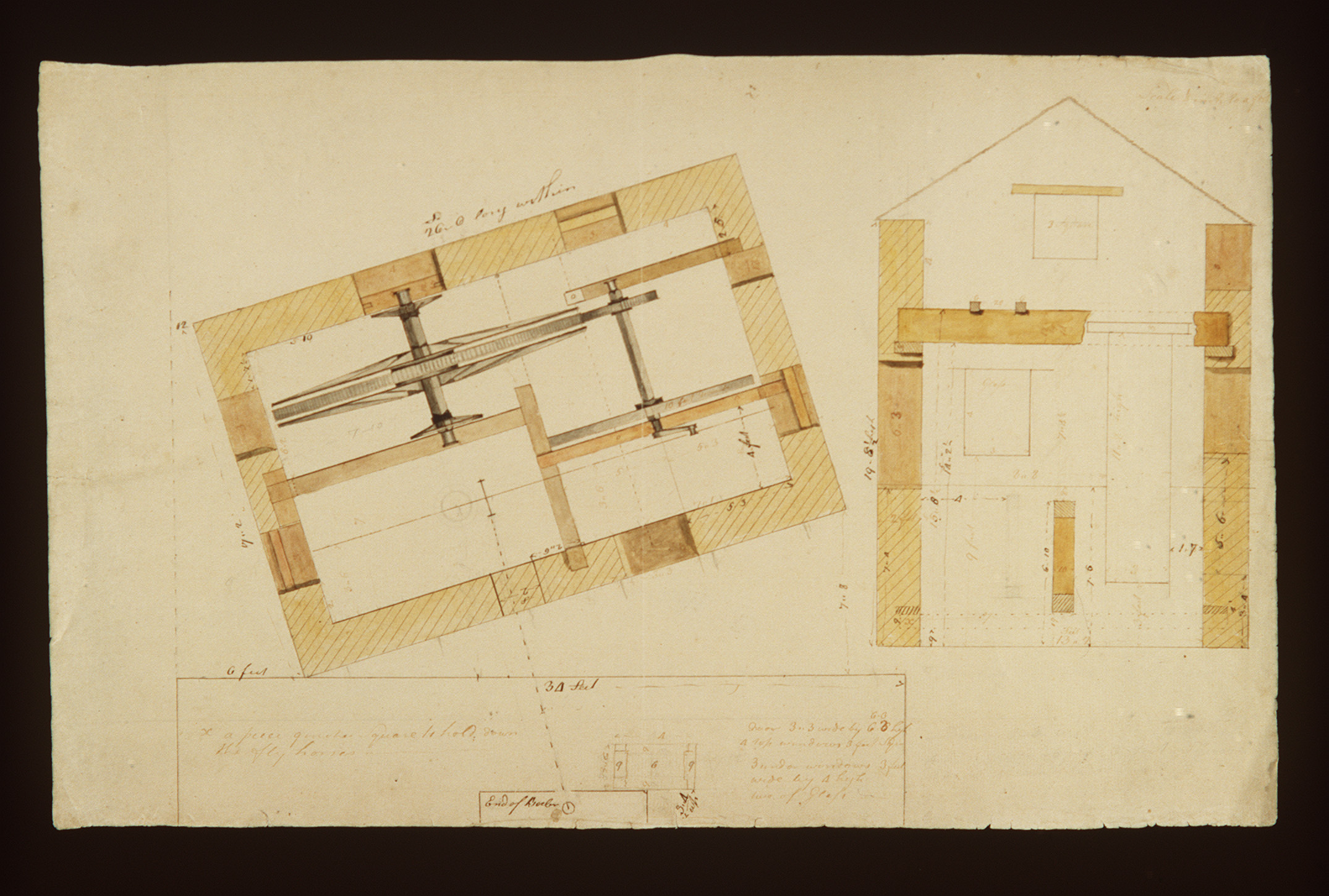

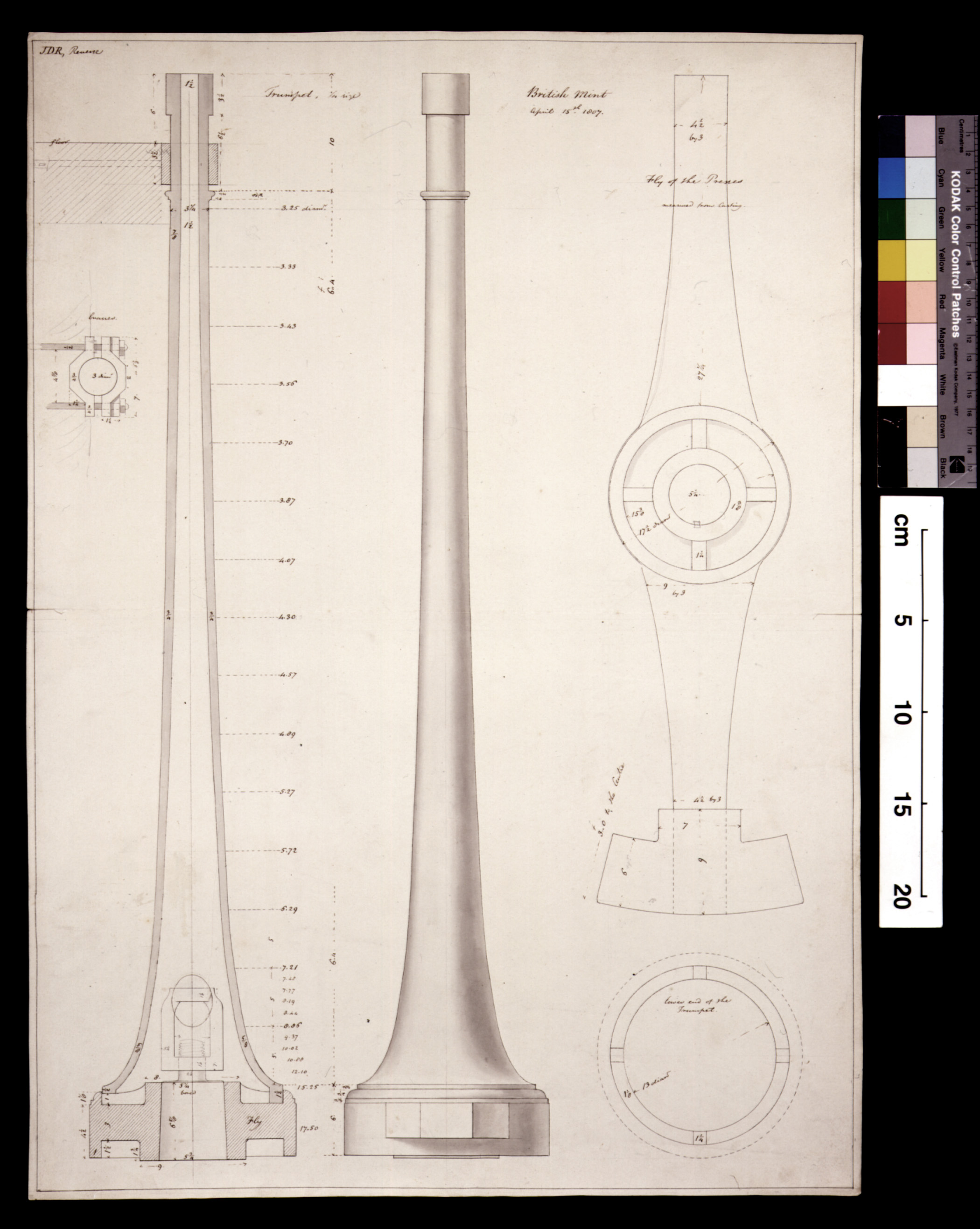

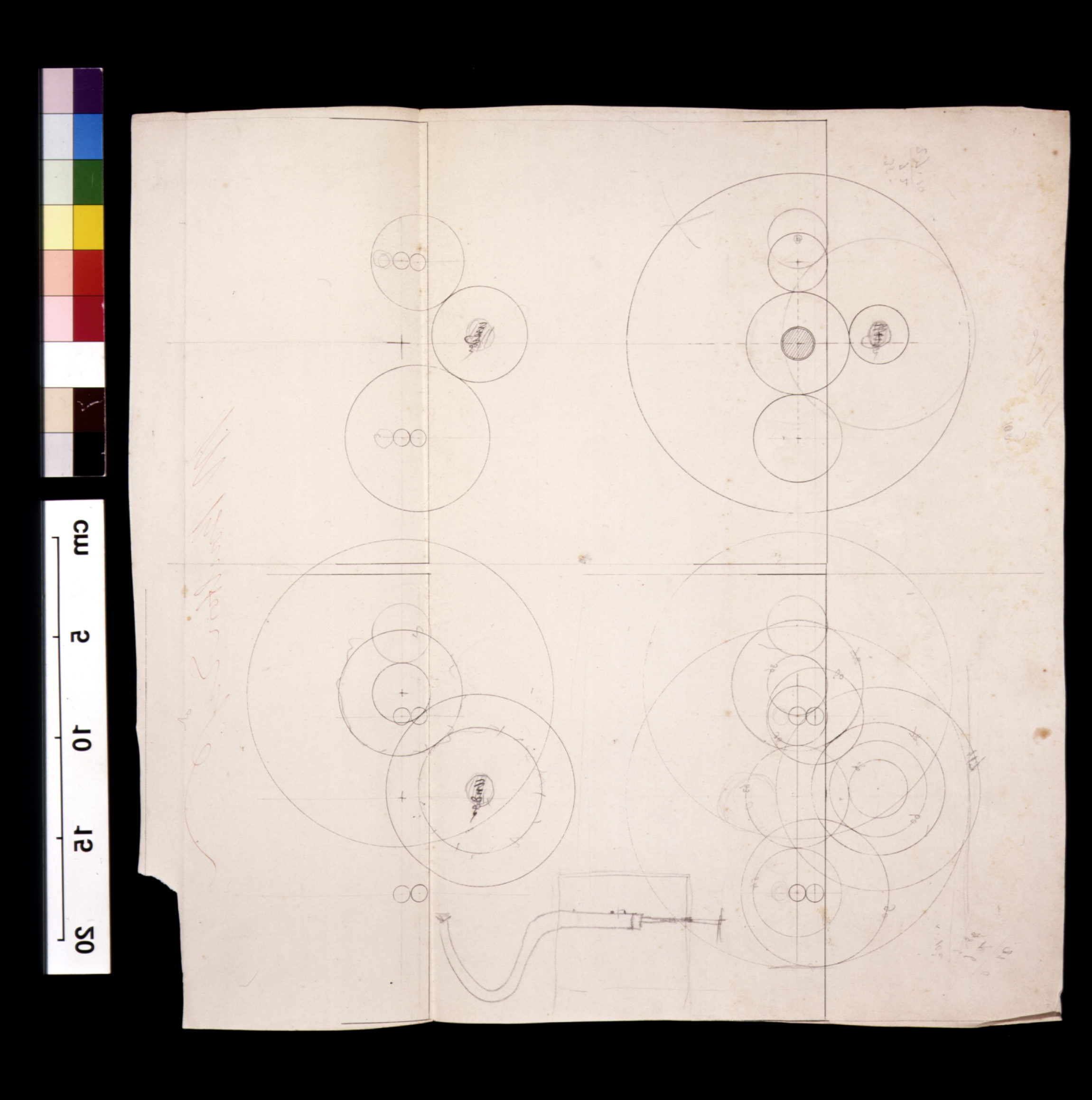

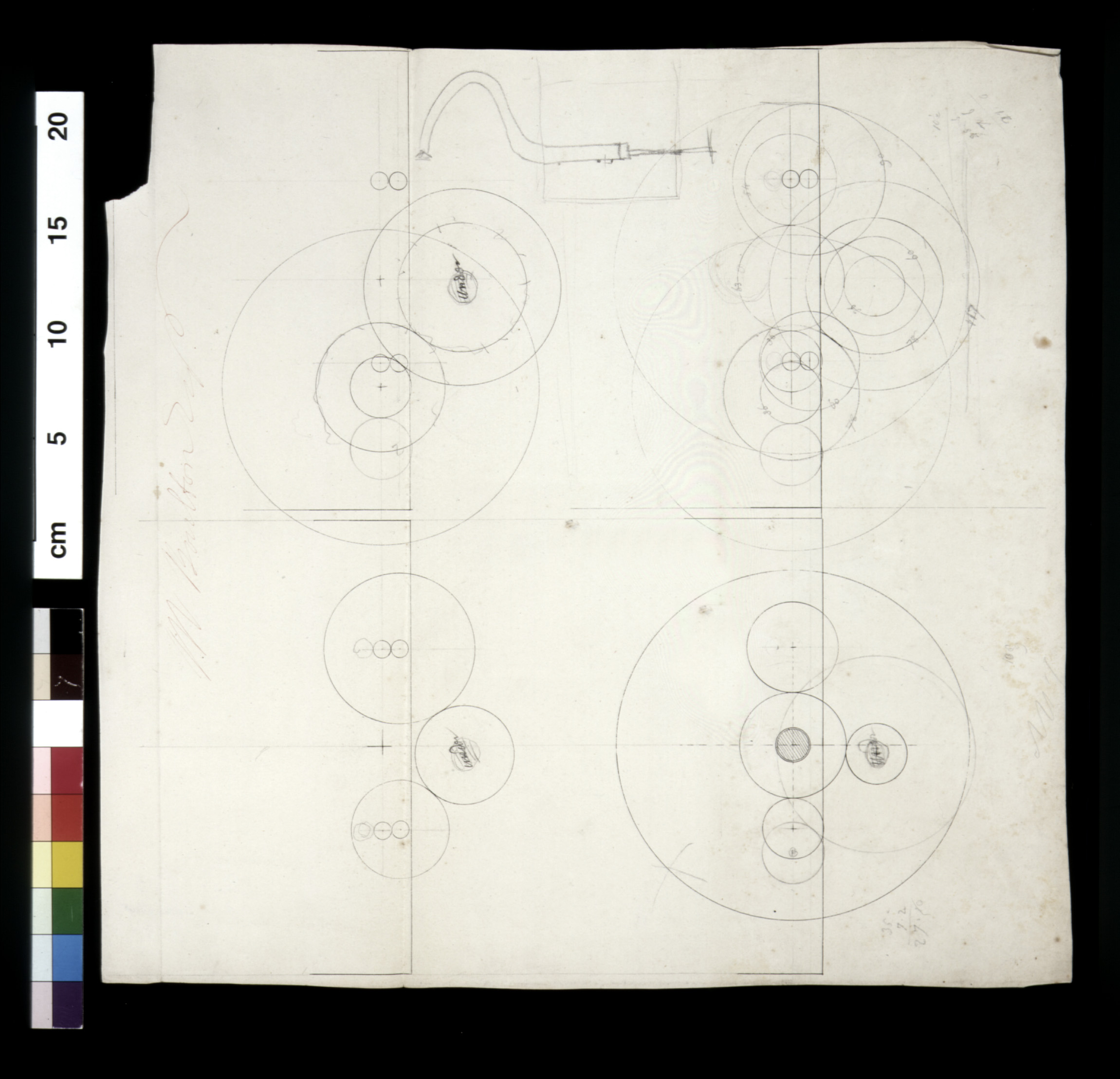

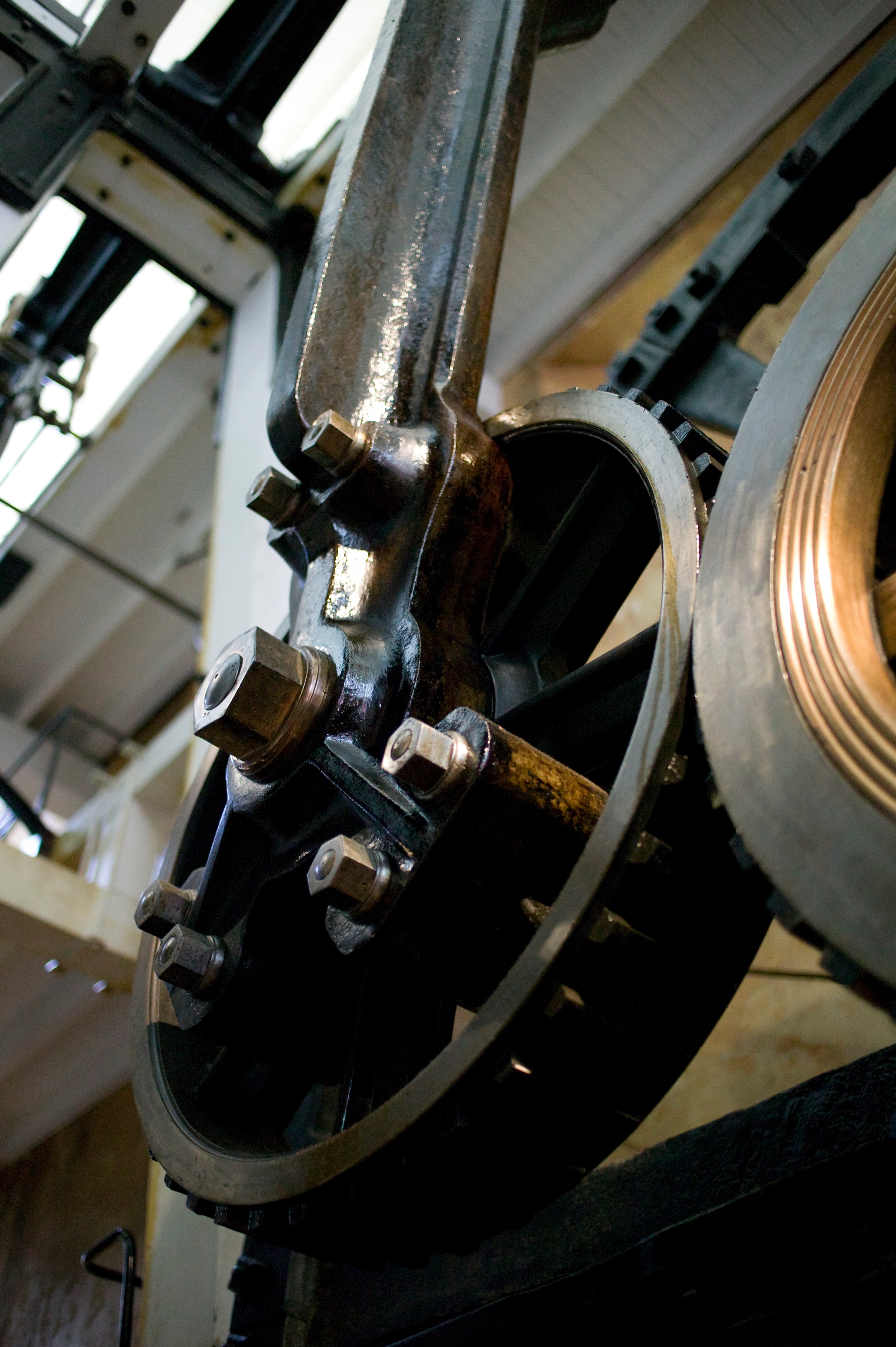

The vertical cylinder is connected to a separate condensor (in a cooling tank with the air pump) to which spent steam is exhausted and cooled to form water, creating a partial vacuum. The piston, which is pushed up and then down by steam admitted to the cylinder below and then above it, is attached to the overhead beam via a set of 'parallel motion' linkages; this mechanism translates the vertical motion of the piston into the arc-wise motion of the end of the beam. The other end of the beam (which rocks up and down about a fixed pivot through its centre) transfers motion via a connecting rod to the 'planet' gear, which turns the horizontal drive shaft via the 'sun' gear; the names refer to the fact that the planet gear moves around the sun gear, which rotates but does not change position. A large flywheel, which maintains momentum between strokes, is attached to the horizontal drive shaft, which also carries the smaller toothed drive wheel and the governor pulley. The centrifugal governor controls the engine speed via a throttle (butterfly) valve in the steam supply pipe. Cylinder bore is 635 mm (25 in), piston stroke is 1830 mm (6 ft), flywheel diameter is 4270 mm (14 ft), and the mass of the cast iron beam is 9.2 tonnes. Steam admission to the cylinder is via drop (poppet) valves, and a flap valve opens and closes the pipe between the condenser and the air pump.

DIMENSIONS

Height

8400 mm

Width

10250 mm

Depth

5200 mm

Weight

33000 kg

PRODUCTION

Notes

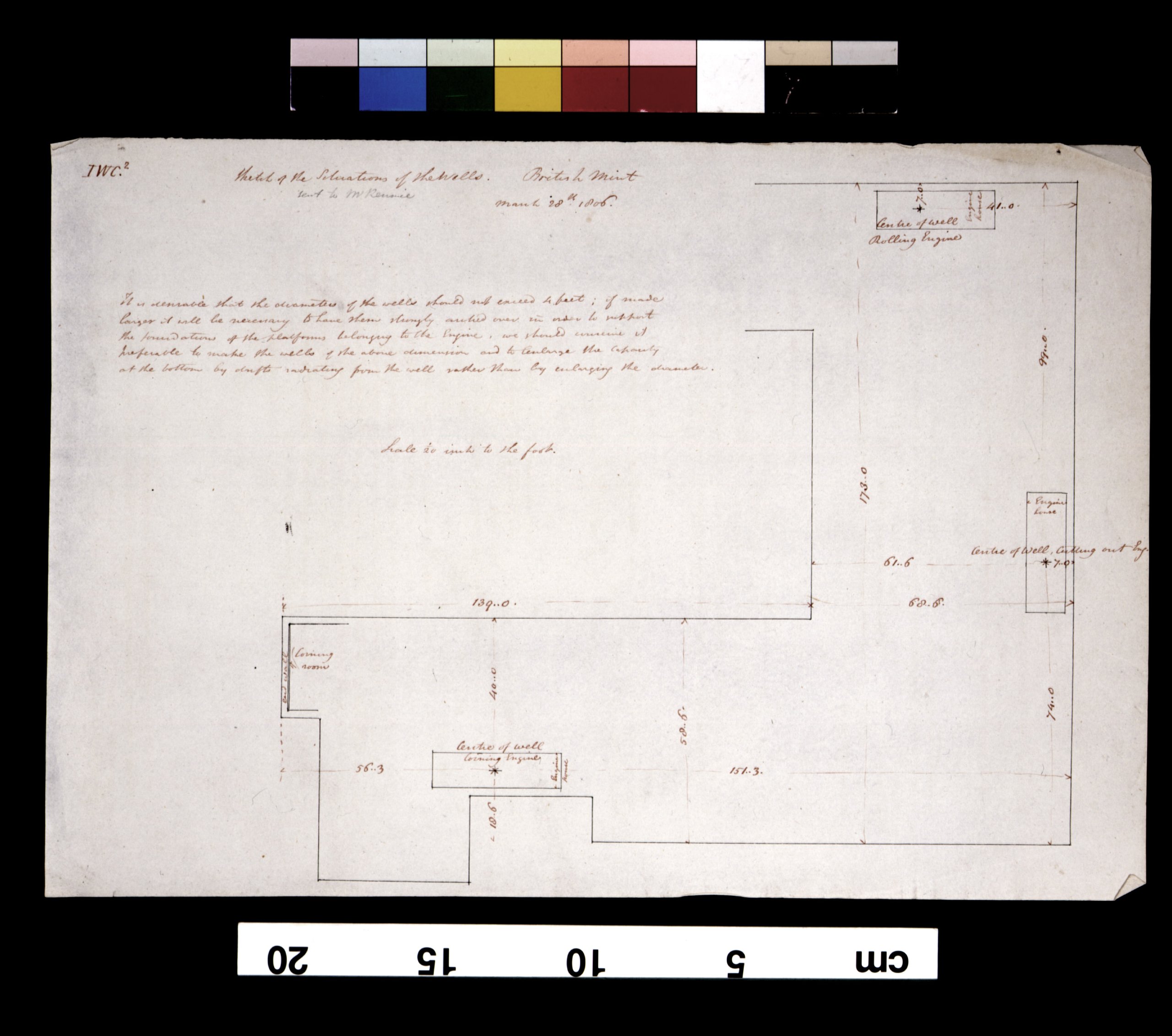

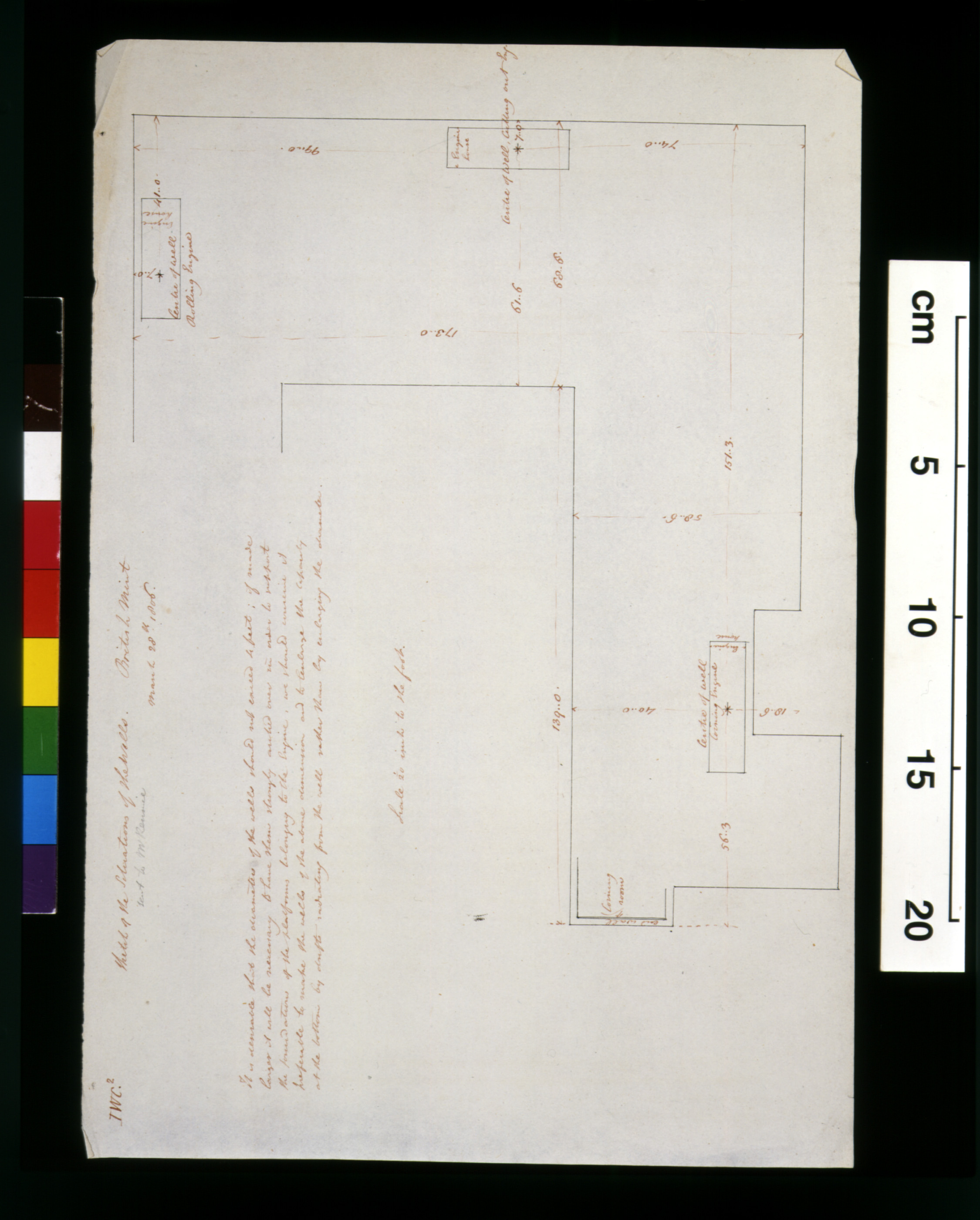

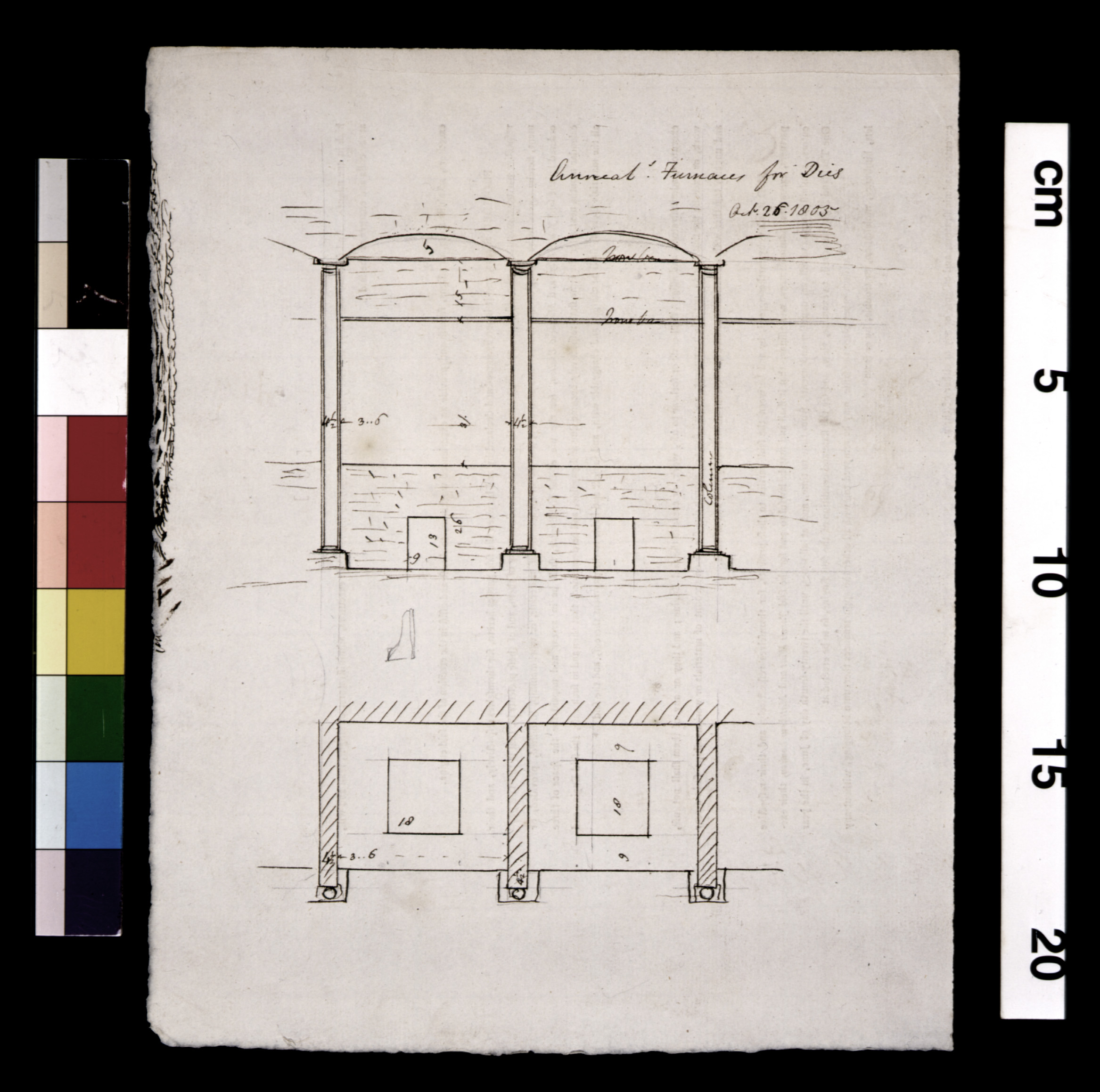

The engine was designed by James Watt, with some assistance from his partner Matthew Boulton and his assistant William Murdoch. It was one of the earliest rotative steam engines to be made and perhaps the sixth by the firm of Boulton and Watt, having been installed in 1785. In all, the company produced about 500 engines, with around 60% of them being rotative. In 1785, Boulton and Watt did not have a foundry of its own and made only the small precision parts such as the valves, at Boulton's Soho Manufactory in Birmingham. The original cylinder and piston were made by John Wilkinson at Bersham in Wales, and the flywheel was made at a London foundry. At that time, Wilkinson's was the only works where a cylinder could be bored with sufficient accuracy to ensure a good fit for the piston, using a machine designed for boring cannon. The beam, connecting rod and water tank were all originally made of wood. Although an early drawing for the engine shows a chain connecting the beam and piston rod, there is documentary evidence that it was actually one of the first engines to have a parallel motion mechanism as original equipment. In 1795, the engine was converted from single-acting (steam operating only on one side of the piston) to double-acting (steam operating on both sides of the piston). This entailed a major refit, with a new cylinder and piston, all new valve gear, extra timber added to strengthen the beam, and an extra layer of cast iron bolted to the flywheel's rim; the engine's power was increased by this means from 10 to 15 horsepower. The new cylinder and piston were made at Coalbrookdale, as Boulton and Watt had heard that Wilkinson was making separate condenser engines without its permission. The governor was retrofitted in the 1790s. The cast iron beam and connecting rod would have been made at Boulton and Watt's Soho Foundry (established in Birmingham in 1796), and the parallel motion (more elaborate than the version shown in drawings dated 1795) would probably have been made at the same time, probably in the 1830s. The cylinder now in place was probably made in 1839 at the Soho Foundry. The iron tank was probably cast in London. There are lines visible on its front panel left by the edges of the wooden planks when they were laid down in sand to make a mould for casting the molten iron.

HISTORY

Notes

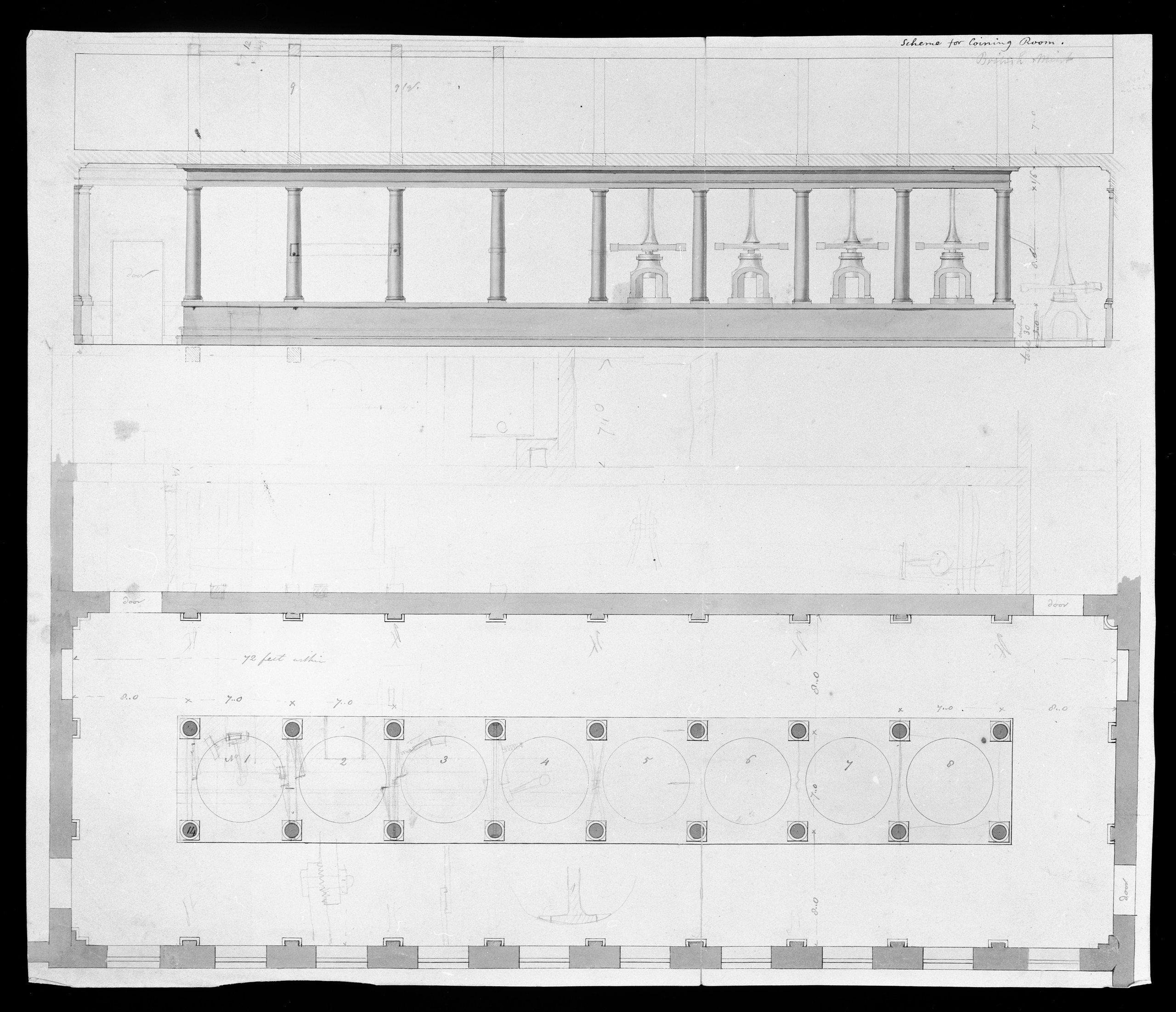

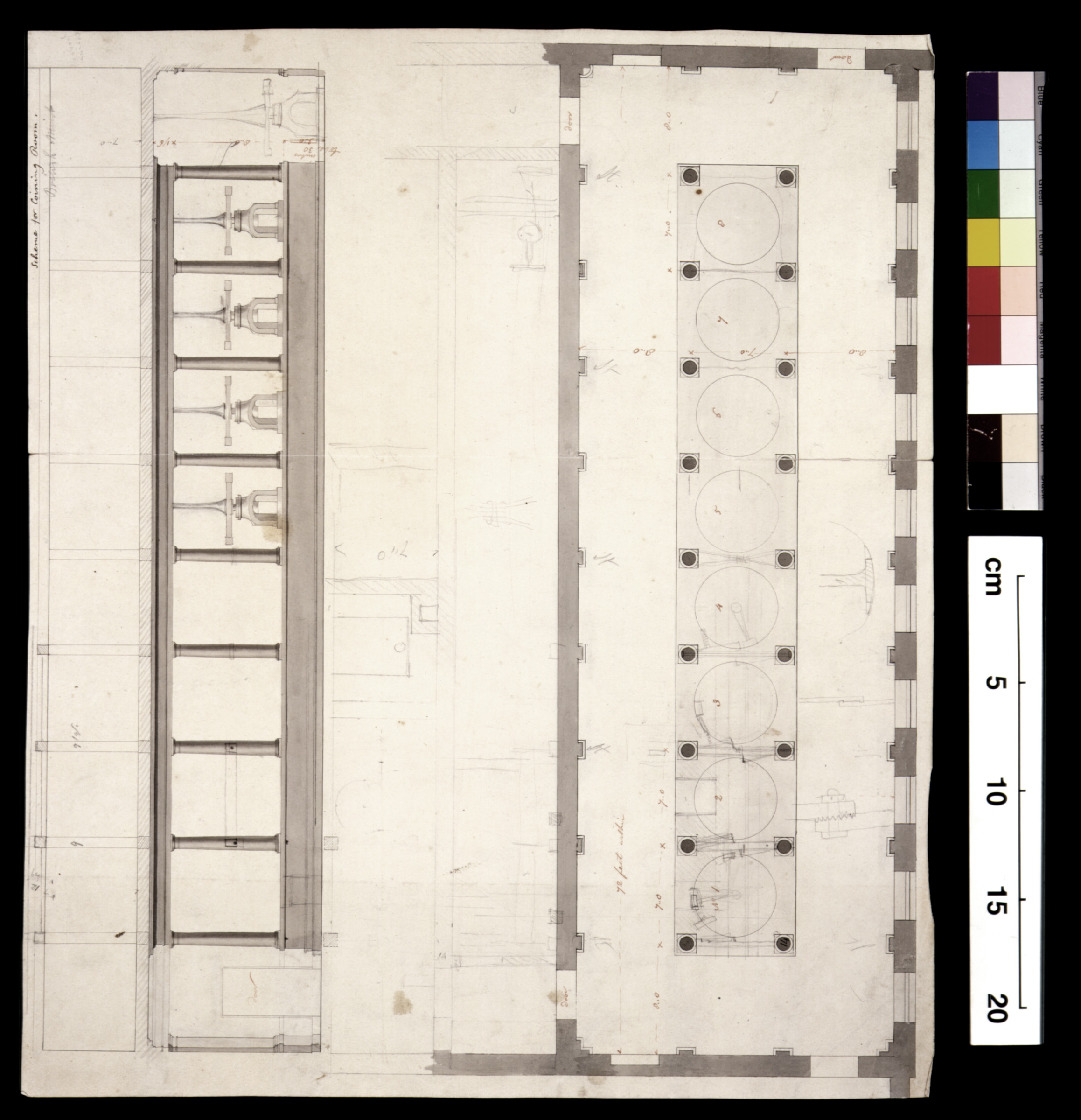

The engine was ordered by Samuel Whitbread in 1784 to replace a horse wheel at his London brewery (on Chiswell Street). It was installed in 1785, but the horse wheel was retained for many years in case the engine needed repairs during the brewing season. Via a series of gears and wooden shafts, the engine's drive wheel turned the rollers that crushed malt, an Archimedes screw that lifted the crushed malt into a hopper, a hoist that lifted bags of malt into the building, a three-piston pump and a device for stirring the contents of a vat. There was also originally a pump working off the engine's beam that lifted water from a well in the brewery yard to a tank on the roof. In 1787 King George III and Queen Charlotte visited the brewery. This was a marketing coup for Boulton and Watt as well as for Whitbread. The engine was originally rated at 10 horsepower. When it was made double-acting in 1795, the owners were offered the choice of having it produce 15 or 20 hp. They chose 15 hp as this meant they paid a lower annual premium to Boulton and Watt. During the term of Watt's patent, the firm charged engine owners an annual premium; this kept the up-front cost of their engines low and eventually made both Boulton and Watt wealthy. The premium was based, in the case of a pumping engine, on the saving in fuel compared to a Newcomen engine doing the same job. For rotative engines, the premium was based on power. The engine remained in service for 102 years. In 1887, Professor Archibald Liversidge of the University of Sydney was visiting London and heard that it was to be scrapped. As one of the founders of Sydney's then Technological, Industrial and Sanitary Museum (the forerunner of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, the parent body of the Powerhouse Museum), he requested that the engine be donated to that institution. The owners concurred and packed the engine for dispatch on the sailing ship Patriarch. To make the flywheel easier to lift and less likely to break in transit, its boss was cut in half and some of the rim sections were dismantled. A shortage of funds meant it was several years before the engine was re-erected, in a brick engine house behind the Museum's headquarters on the site of Sydney Technical College. Some years later, an electric motor was attached to turn the flywheel, so that visitors could see the engine in motion. In the 1980s the Technology Restoration Society was set up to raise funds for the engine's restoration to steaming order. The work was carried out by staff and contractors at the Museum's Castle Hill site. The engine was installed at the Powerhouse Museum in 1988.

SOURCE

Credit Line

Gift of Messrs Whitbread & Co, Brewers, 1888

Acquisition Date

5 June 1888

Copyright for the above image is held by the Powerhouse and may be subject to third-party copyright restrictions. Please submit an Image Licensing Enquiry for information regarding reproduction, copyright and fees. Text is released under Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivative licence.

Image Licensing Enquiry

Object Enquiry