Sydney Monorail station turnstile controller board

Object No. 2014/13/6

This is a microprocessor controller for turnstiles from one of the eight stations on the Sydney Monorail. This controller had software which provided information on the number of tokens inserted and when it was time to empty the token bag. The Sydney Monorail was a controversial limited public transport system which operated on a 3.6-km elevated single continuous loop track connecting Darling Harbour and Chinatown with Sydney's central business and shopping districts between 1988 and 2013. The public could get on the Monorail initially from six but later eight stations. These were all fully enclosed constructions of steel and glass (some in private ownership). The platforms were designed to accommodate one train, approximately 27 metres in length, and be accessed and exited by turnstiles which were operated by tokens or smart cards. All stations were furnished with public address systems and, for security reasons, were supervised by closed circuit television surveillance cameras. Screens located in the Central Control Room of the Monorail's depot at Pyrmont monitored the stations. The Sydney Monorail system was originally designed to operate in fully automatic mode. Not only were stations and substations meant to be unstaffed but trains were supposed to operate by themselves. However, problems with vending machines for tickets and smart cards saw it necessary for them to be permanently attended in kiosks to sell tokens for the turnstiles and access to the station platforms. The trains also needed operators to ensure reliability of service. The Monorail was touted as a 21st century transport system for Sydney but ended up being an entertainment ride for tourists. It was fundamentally flawed in its route and failed to attract commuters who made up only 9 percent of its passengers. If the government at the time had installed a light rail system, as was the official recommendation, Sydney may have had the beginnings of a modern public transport system in the city then instead of being decades behind as is the case today (2013). The Monorail was purchased by the NSW State government in 2013 in order to close and demolish it. The last day of operation was Sunday 30 June 2013. "The Darling Harbour Monorail: Linking the City to Darling Harbour". Evans, David, 'It's The Rail Thing', in "Daily Mirror", 7 May 1987, p.26-7. Evans, David, 'Mountains out of monorails' in "Daily Telegraph", 24 May 1987, p.8. "Gem 80 Minigem Technical Manual", GEC Industrial Controls Ltd, Kidsgrove, Staffordshire, England, 1986. "Monorail Autopilot Training Course Manual", ANSYS Pty Ltd, 1994, pp. 64-67. Office of Transport Safety Investigations, "Rail Safety Investigation Report Monorail Collision Darling Park 27 February 2010". Saulwick, Jacob, 'Never the rail deal', in "The Sydney Morning Herald", 18 June 2013. "The Sydney Monorail, TNT Harbour-Link: moving with Sydney into the 21st Century". https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Von_Roll_Holding wiki Von Roll Holding. Margaret Simpson Curator, Transport October 2013

Loading...

Summary

Object Statement

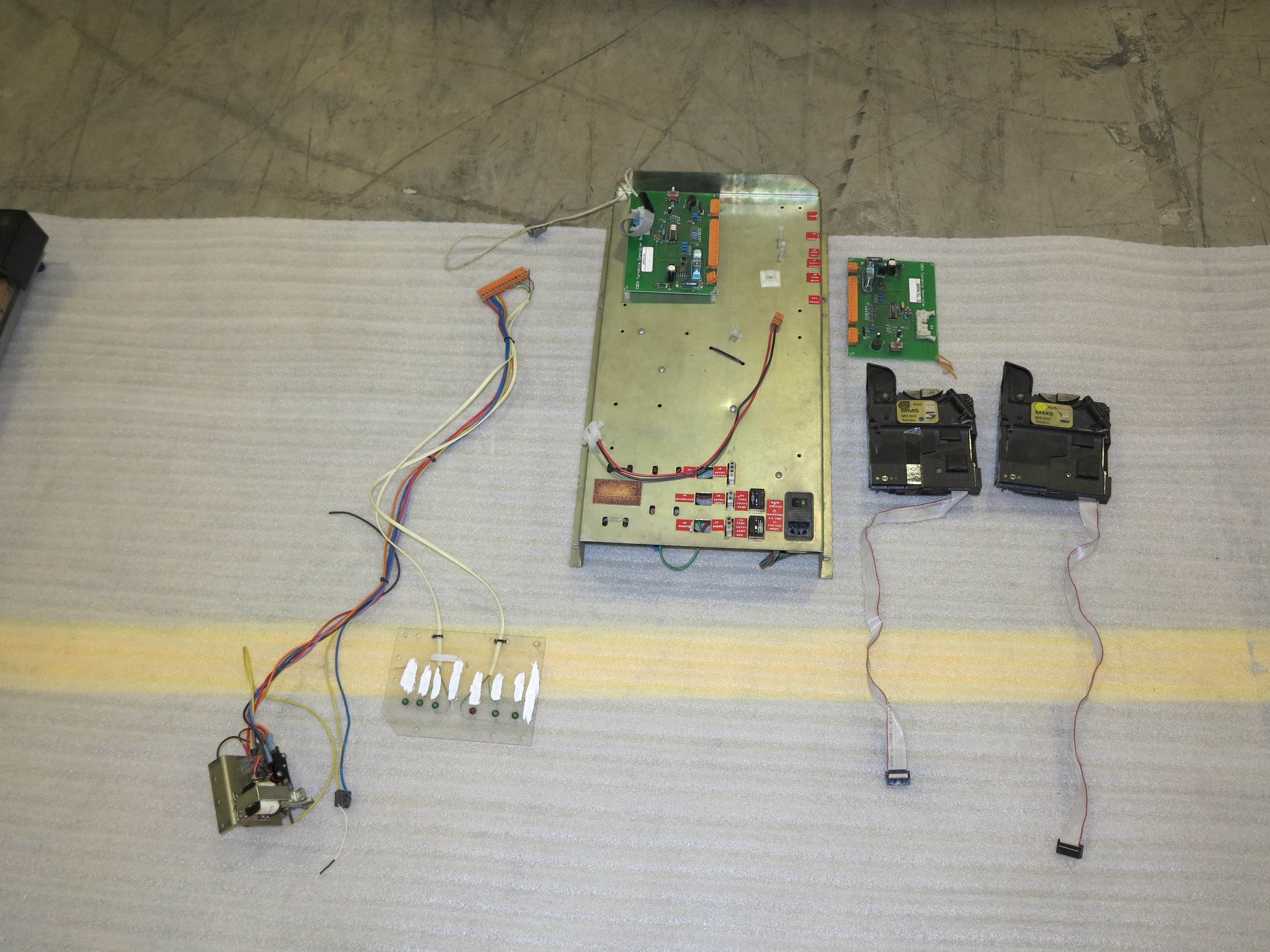

Turnstile controller board and manual, from a Monorail station, made by CGEA Transport Sydney Pty Ltd, used on the Sydney Monorail, Darling Harbour and Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 1988-2013

Physical Description

This controller comprises a microprocessor board based on a 16F84 microcontroller chip. Forty-eight volts DC from the power supply was fed to a simple 24 volt stabilising circuit. The 24 volts were used for the coin acceptor and was further regulated to 5 volts in the IC1. The 48 volt power source was also used to run the solenoid in the turnstile as well as the relay RE1 and fed the card reader. The manual comprises four A4 pages stapled together and is entitled "Manual Turnstile Controller Board".

HISTORY

Notes

Planning The redevelopment of the Sydney Darling Harbour area was announced in May 1984 by the Labor Premier, Neville Wran. It comprised the $200 million transformation of a 50-ha site of derelict railway sidings and industrial buildings around Cockle Bay, west of Sydney's CBD. In early 1985 the Darling Harbour Authority received over 20 expressions of interest for a people mover proposed to link the city with the redevelopment. A shortlist of entrants was then invited to submit their plans which in the end came down two proposals. On 28 October 1985 the NSW Minister for Public Works, Laurie Brereton, officially announced that Sir Peter Abeles' TNT company, a logistics giant, won the contract for its proposal of a driverless, single track, elevated monorail to be built at no cost to the government. (The other proposal was a two-way light rail which would have connected Pyrmont, Circular Quay and Central stations.) Contracts for the Monorail project were signed in March 1986 at a projected cost of $60 million. Clearly, Wran and Brereton had not consulted an "Encyclopaedia Britannica" (1980) readily available in every local library. If they had they would have read that "the money savings achieved by building elevated lines has been shown to represent false economy in the long run because of the damaging effects of elevated structures on business and residential streets. Though arguments have been advanced that aesthetically pleasing and quiet monorail lines could be built in city streets, present experience is not favourable. Though most fairs of recent years have had monorail systems, and Dallas has a short line connecting the airport parking area to one passenger terminal, no successful system has been built for a central business district." Darling Harbour became Australia's premier urban redevelopment project which opened in 1988 for the Australian Bi-Centenary. At the time it was envisaged to be focal point for the city's leisure activities for both Sydney's visitors and workers. The Monorail was seen as a vital connection between major cultural and tourist venues including the Powerhouse Museum, Australian National Maritime Museum, Entertainment Centre, Sydney Convention Centre, city hotels, Paddy's Markets, Chinatown and the Harbourside Festival Markets. The Monorail was promoted as beginning an exciting era in rapid transit as passengers could glide effortlessly above street congestion and avoid crowded city thoroughfares on their way to the festive atmosphere of Darling Harbour. It was argued that by building "a quiet, electric monorail this contributed to the serenity of Darling Harbour…[and] enabled planners to leave large sections…as open space for the safety and enjoyment of pedestrians at Darling Harbour." Protest In protest against the planned construction of the Monorail, Sydney Citizens Against the Proposed Monorail (SCAPM) was formed in December 1985 with its legal adviser, the solicitor and sustainable house owner, Michael Mobbs. During 1986 SCAPM appealed to the public in newspaper advertisements to support its stand and held anti-monorail protest meetings and fundraising concerts at the Sydney Town Hall and marches through the streets attended by thousands. The protest group made submissions to public inquiries held to determine the course of the elevated track and wore protest badges promulgating their objections: 'QVB yum - Monorail yuk'; 'No Monorail'; 'Stop the Monsterail'; 'Who needs a monorail? I've got feet!'; 'Sydney Citizens Against the Proposed Monorail'; and after it was built, 'Dismantle the Monorail'. Some of the more high profile protesters included the country's cultural elite, Peter Carey, Leo Schofield, Jim McClelland, Margaret Roadnight, Ruth Cracknell, Ita Buttrose, Mike Carlton, Nick Greiner and Patrick White who described the proposed monorail as "one of the many autocratic farces perpetuated by the powerful on our citizens." Urban activist, Jack Mundy, said it "represented the rape of the city." Many architects and planners were also against the Monorail, as were some government officials. Clover Moore, then an Independent MP, called it "the most offensive structure to assault our city since the Cahill Expressway" whilst architect, Harry Seidler, announced "it was the most tragic thing that happened to the urban fabric of Sydney". The National Trust of Australia (NSW) argued that numerous historic buildings in the City were damaged during the Monorail's construction and the whole system was visually at odds with Sydney's historic streetscape. Ironically when it opened the Monorail was promoted as the ideal way to see some of Australia's finest historical architecture including the Queen Victoria Building, Sydney Town Hall and Pyrmont Bridge. Testing and Opening Testing of the Monorail began in May 1988 and the system officially opened to the public on 21 July 1988. It was originally intended for the Monorail trains to be driverless and for the system to operate automatically. After a number of breakdowns due to problems with the sensitive electronic controllers perceiving obstacles such as leaves on the track it was decided to have human eyes monitoring the track so operators permanently occupied the first carriage. Initially, the operators had to stand up, and then were given a stool and later still a chair. Once operators occupied the cab this car was no longer open to the travelling public. After its opening there was an enthusiastic flurry of monorail proposals for other routes around Sydney including above the major road arteries of the Hume Highway, Victoria Road, Barrenjoey Road, Military Road and Parramatta Road as well as a spur line from the proposed new airport at Badgerys Creek and even over the top of the arch of the Sydney Harbour Bridge! Operation The trains operated simultaneously in the same anticlockwise direction along the single elevated track. Initially six trains ran at a frequency of every 2 minutes between services. The trains stopped at stations for about 40 seconds, which included time to decelerate, board passengers and accelerate. A complete circuit of the 3.6 km loop took 12 minutes and the operating speed was 33 kph. The system had a total capacity of 5000 passengers per hour with each train seating 48. Ron Ward was the general manager of TNT Harbourlink and ran the Monorail for the first 10 years. There were five operational managers, Wayne Ferguson, Greg Glancy, Rob Butterworth, Paul Ivers and Warwick Talbot. Ferguson became the Monorail's first marketing manager and developed a Smartcard for regular Monorail users. It was the first debit card fare system in Australia. His inspiration for it was the magnetic strip on his library card. Vending machines were installed at the Monorail stations for passengers to purchase cards and top them up. This was years before the Opal card was introduced in parts of Sydney in 2013. The operation of the Monorail system was controlled from a control room located above the maintenance facility in Pyrmont. A control panel operator oversaw the operation of the system via a computer mimic panel known as a Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) system. This showed the real time position and performance of each train around the track. The controller was able to talk to each driver by two-way radio and also had voice contact with each car in each train. By the end of its operational life the cost of the Monorail was a very expensive form of public transport. A blanket fare of $5.00 was charged to travel to only one station or the entire circuit. As token vending machines were unreliable tokens were purchased from a ticket office or kiosk at each station and fed into turnstiles to admit passengers onto the platform. The operating hours were from 7 am to 10 pm Monday to Saturday and 8 am to 10 pm on Sunday. The Monorail operated every day of the year except Christmas Day. There was no actual timetable but with four trains operating the wait between services was only a few minutes. The Monorail's Eight Stations The Monorail was accessed initially from six but later by eight stations. These were all fully enclosed constructions of steel and glass. The platforms were designed to accommodate one train, approximately 27 metres in length, and accessed and exited by turnstiles. All stations were furnished with public address systems and, for security reasons, were supervised by closed circuit television surveillance cameras viewed in the central control room at Pyrmont from where public announcements could also be made. The stations comprised: Harbourside- this station was located at the western end of Pyrmont Bridge next to the Harbourside shopping centre in Darling Harbour. Convention - this station was located on the western edge of Darling Harbour and served the Sydney Convention and Exhibition Centre. Paddy's Markets - this station was located beyond the southern end of Darling Harbour near the Entertainment Centre and Paddy's Markets. It was originally named Haymarket but later changed to Powerhouse Museum before changing to Paddy's Markets. Chinatown - this station was originally proposed to be called Darling Walk, then Gardenside. It ended up being called Garden Plaza but was later renamed Chinatown. Between 26 July 2004 and 18 December 2006 the station was closed all together. In 2010 its hours of operation were only between 7 am and 9 am on weekdays. Word Square - this station was located in Liverpool Street between Pitt and George Streets. It was originally proposed to be called City South. A temporary station was in use from late 1988 until 2005 when the station was rebuilt into the new adjacent building. Galeries Victoria - this station was originally proposed to be called Town Hall but was named Park Plaza instead. A temporary entrance was provided from the opening of the service in 1988 until 2000 when the station was incorporated into the new adjacent building. City Centre - this station was near the corner of Pitt and Market Streets. It was only a temporary one from opening in 1988 until mid-1989 during construction of the City Centre shopping arcade. The temporary station was partly suspended above Pitt Street. Darling Park - this station was near the eastern end of Pyrmont Bridge and was originally proposed to be called Casino but Sydney's casino was eventually built in Pyrmont. Power Distribution System Operating power for the Monorail system was derived from an 11 KV feed provided by the local electricity authority at a substation near the maintenance and control facility at Pyrmont. Propulsion power and "housekeeping" power around the system were provided by substations along the route and fed from the main 11 KV substation. Power for the trains was distributed along the track over plastic sheathed aluminium collector rails fitted to the sides of the track just below the running surface. Copper collector shoes on sprung arms fixed to the rear carriage bogie ran inside the collector rails to draw off power. Each train had its own power back-up batteries to ensure the continued operation of selected vital equipment such as emergency communications and carriage ventilation. In the event of a loss of substation power, an automatically-activated diesel-powered emergency generator in the maintenance facility applied sufficient capacity to the system to bring stranded trains safely into stations one-by-one. Communication All communication with trains was by radio. Bi-directional data and voice communications was achieved over three duplex channels. One channel carried "transmit" and "receive" voice signals to all carriages in all trains. This allowed one passenger to speak to the control room at a time, with others being put automatically into a queue. The other duplex channels were dedicated to gathering data from and distributing data to trains, with one channel allocated to train Nos 1, 2 and 3 for transmission reception and the other to train Nos 4, 5 and 6. The Australian firm, AWA, undertook the original voice communication system for the Monorail. As more and taller city buildings were constructed the direct line of sight was broken and the communication system developed black spots. Operating Monorail Trains Monorail trains could operate in three modes: Automatic, Semi-automatic, and Manual. In Automatic mode an unattended train could be pushed onto the track loop by the traverser at the depot. The Control Operator in the control tower closed the doors and dispatched the train which was then meant to travel around the loop automatically, docking at stations and collecting and unloading passengers. All operations were performed automatically including door opening and closing, speed, time spent at stations and other functions. A train in "Semi-Automatic" mode had an operator in Car No.1 who manually gave the door "close" command and the train the "go" command. Beyond this the train operated automatically. The semi-automatic mode assisted in maintaining a safe operating distance between trains, automatically adjusted the train's speed and stopped it when the distance to the train ahead was reduced to below the pre-determined limit of 100 m. Operating the train in semi-automatic removed a number of risks associated with driver error. (The Autopilot operated the same regardless of the train being in automatic or semi-automatic). In "Manual" mode a driver was required to manually control the speed and other functions of the train. Manual driving was repetitive with frequent braking and control tasks to be completed at each station. It was generally used for only a small part of the day's operation which was mostly spent in semi-automatic mode. A keyboard switch on the consol in the leading car was used by the driver to switch between the modes as instructed by the Control Operator in the control room. The Sydney Monorail system was originally designed to operate in fully automatic mode. Not only were stations and substations meant to be unstaffed but trains were supposed to operate by themselves including stopping at stations, opening and closing doors, departing from stations, accelerating, intelligent speed control, decelerating, anti-collision and anti-bunching control without the need for human intervention. Even so, the leading car was still fitted with a control consol for putting the trains into and out of service and during maintenance. However, from the start, the Automatic mode of operating was plagued with problems.

SOURCE

Credit Line

Gift of Transport for NSW, 2014

Acquisition Date

29 January 2014

Copyright for the above image is held by the Powerhouse and may be subject to third-party copyright restrictions. Please submit an Image Licensing Enquiry for information regarding reproduction, copyright and fees. Text is released under Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivative licence.

Image Licensing Enquiry

Object Enquiry