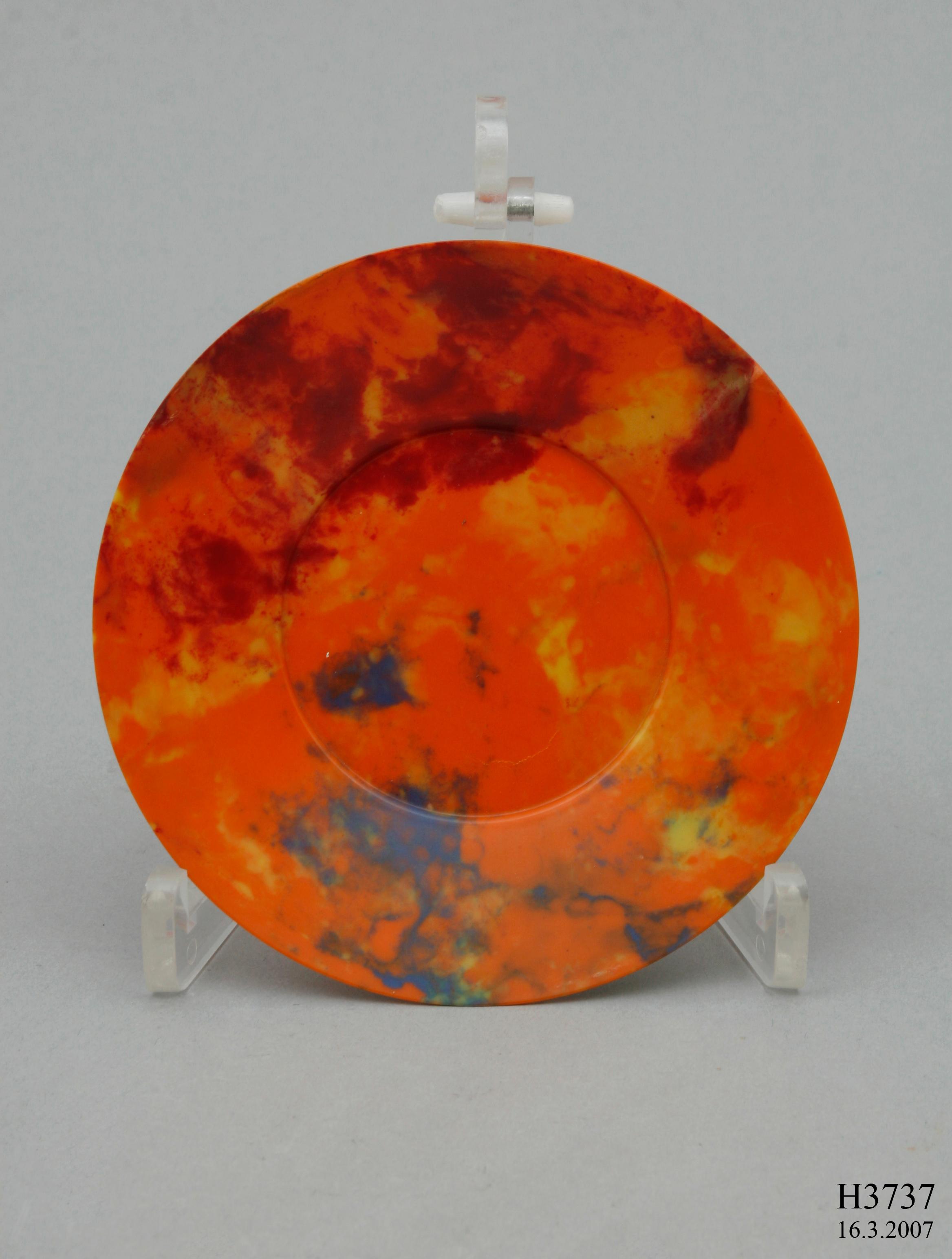

'Harlequin' dessert plate

Object No. H3737

This dessert plate is made of 'Beetle' moulding powders. These urea-formaldehyde powders first appeared in the 1920s and their light swirling colours were used to produce table ware and domestic products. In 1930 an Australian company, the Australian Moulding Corporation, used 'Beetle' moulding powders to create their colourful 'Harlequin' range of table ware that included this dessert plate. This object is part of a large collection of plastics and plastic moulding powders acquired by the museum during Arthur Penfold's career. The collection gives insight into a period of great social, material, technological and scientific development, along with the collecting practices of the museum at the time. Plastics continues to be an area that is explored and represented in the museum's collection, however today reflects some of the more ambivalent attitudes towards plastics and their use, particularly in regards to environmental and sustainability issues. The museum's plastics collection began in the 1930s with the acquisition of specimens of plastic raw materials and finished products. The collection was driven largely by Arthur de Ramon Penfold (1890-1980), a former industrial chemist, who worked as curator and later director of the museum from the years 1927 until 1955. In his 1945 article in the magazine 'Australian Plastics' he described plastics in Australia as " ... an industry so promising in its possibilities [it] deserves the very best quality of personnel in every grade of occupation." (Penfold, 1945) Between 26 and 28 September 1934, the Technical College and the museum collaborated to develop what was advocated as the first Plastics Industry Exhibition in Australia. The museum contributed the majority of the exhibits, including colourful moulded objects and synthetic resin powders. A permanent display of plastics was established at the museum. REF: Penfold, A. R., 'Penfold reports from London', in Cooper, R. B., (ed), 'Australian Plastics', Vol1, No. 4, 1945

Loading...

Summary

Object Statement

Dessert plate, 'Harlequin', urea-formaldehyde plastic, made by Australian Moulding Corporation/Moulded Products (Australasia) Pty Ltd, made in Australia, 1930-34.

Physical Description

A 'Harlequin Ware' dessert plate made from Urea-formaldehyde with a mottled orange, red, blue and yellow surface.

DIMENSIONS

Height

16 mm

Diameter

146 mm

PRODUCTION

Notes

This dessert plate is part of the 'Harlequin' range of table ware made by the Australian Moulding Corporation in 1930. This company was established by John Derham in 1927 and was the first plastics firm in Victoria. They were importing phenolic powder to produce moulded tableware called Saxon Ware; unfortunately it had a bad smell. Derham discovered an imported range of plastic table ware in a Myer store that didn't have a bad smell. He found out the maker and discovered that 'Beetle' urea moulding powders were used to produce the product (Hewat, 1983). He then ordered 'Beetle' moulding powders from Britain and began to use them to manufacture products. This dessert plate was made using 'Beetle' moulding powders. 'Beetle' moulding powders were produced by The Beetle Products Co, a company formed in 1925 through the efforts of the British Cyanide Company's managing director, Kenneth Chance. The resins for this powder were purchased from the British Cyanide Company who had invented 'Beetle' moulding powders. 'Beetle' moulding powders were the result of experiments carried out by the British Cyanide Company's Chief Chemist, Edmund Rossiter, who condensed thiourea with formaldehyde. Samples from this experiment were shown at the Wembley Exhibition in 1925 with beetle logos on the bottles, hence the name. This experimentation with thiourea was the consequence of changes in fashion during the 1920s when weighted silk declined in popularity. Thiourea was used in the production of weighted silk and was supplied by the British Cyanide Company to the silk industry. To make up for financial losses when thiourea was no longer in great demand the company began to experiment to discover new uses for it (Plastiquarian, 2007). The result of these experiments was a water-white synthetic resin; the colour was an advantage because there were no white plastics moulding powders at that time. Early phenolic resins (e.g. Bakelite) could only be produced in a few colours (Hayes, 2007). In the 1930s improvements were made to the manufacture of 'Beetle' moulding powders and urea-formaldehyde resins were used to produce colourful, scratch-proof and glossy consumer goods that were commercially successful and cheap to make. REF: J. Hayes, "From Cyanide to 'Beetle'", in Plastiquarian no. 14 Winter 1994/5, viewed online http://www.plastiquarian.com/styr3n3/pqs/pq14.htm, accessed 02/08/2007. Plastiquarian, 'Thiourea formaldehyde', available at http://www.plastiquarian.com/thiourea.htm, accessed 03/08/2007. T. Hewat, The Plastics Revolution: The Story of Nylex, The Macmillan Company of Australia Pty Ltd, Victoria, 1983, pp. 26-27.

HISTORY

Notes

Plastics have been described as "materials that can be moulded or shaped into different forms under pressure or heat." They were a cultural phenomenon in the twentieth century when they changed the way objects were produced, designed and used. It was also in the twentieth century that most plastic products moved away from natural raw materials to synthetically produced ones. Before the arrival of synthetic resins natural plastics such as amber, horn, tortoiseshell, bitumen, shellac, gutta-percha and rubber were used to mould and manufacture artefacts. Horn was the most used of these products and by 1600 moulding was being used to produce horn products. This ability to mould products quickly and cheaply rather than carve them became the prime motivating force behind the development of plastics. By the middle of the nineteenth century tortoiseshell and ivory were becoming expensive and this encouraged the search for alternate materials. In 1852 Alexander Parkes developed cellulose nitrate into a mouldable dough he called Parkesine. By 1860 it was being pressed into moulds to make billiard balls, pens, and even artificial teeth. By 1900 there were a number of plastics being produced but it was still a relatively small industry and as Susan Mossmann, an historian of plastics states " ... a typical middle-class family would encounter few plastics as they went about their daily business. Perhaps women would wear Celluloid combs in their hair, or carry Celluloid evening bags. If in mourning, they might wear artificial jet jewellery made of Vulcanite, have celluloid or casein cosmetic boxes and use celluloid backed brushes and mirrors." (Mossmann, 1997) By the end of the twentieth century most of these products had been replaced by synthetic plastics. Others found niche markets and lasted for longer such as the use of shellac to make gramophone records which lasted into the 1940s. The first fully synthetic plastic was developed in early twentieth century by Leo Baekeland. His new plastic was named Bakelite and heralded in a new era as this plastic was not only lighter than metal it could be made into a wide variety of objects traditionally made from wood or metal. During the First World War Bakelite was used for electrical insulators such as plugs and switches as well as Thermos flasks and cigarette boxes. In the 1930s there was a surge of interest in plastics and plastic products particularly coloured Urea-formaldehyde laminates. These products had excellent temperature resistance but, unlike early Bakelite, could be produced in different colours. This object is made of an early plastic moulded from urea-formaldehyde resin powder. The most popular form of this powder was first marketed in 1928 by the British Cyanide Company as 'Beetle' powder. However within a few years there were a range of other companies manufacturing similar thiourea/urea products such as 'Pollopas', 'Resopal' and 'Cibanoid'. These products were less resistant to water and allowed coloured effects but they were also more susceptible to heat than many other plastics. One noticeable feature of products such as lampshades and electrical fittings using this material is the very distinct smell they give off when decomposing. Dunlop-Perdriau Rubber Co Ltd donated this dessert plate and a number of other items to the museum in 1934. Henry and Stephen Perdriau were among the first in Sydney to pioneer plastic products in Sydney. In 1885 Henry began importing rubber for railway carriage buffers and as demand increased he opened a plant at Drummoyne, Sydney, and by 1888 was an agent for English, German and American rubber companies. Increasing demand and protection after Federation resulted in the formation of the Perdriau Rubber Co. Ltd in 1904. The company amalgamated with the Dunlop Rubber Co. of Australasia Ltd in 1929. Dunlop-Perdriau gained a controlling interest in Moulded Products Pty Ltd (previously Australian Moulding Corporation) from 1934 until 1937 when it sold off its interests in the company. REF: Mossman, S., (ed.), Early Plastics; perspectives, 1850-1950, Leicester University Press, London, 1997, p.6. Mossman, S., Morris, P. J. T., (eds.), 'The Development of Plastics', Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, 1993 Kaufman, M., 'The First century of Plastics', The Plastics and Rubber Institute, London, 1991? Australian Dictionary of Biography, available at http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A110206b.htm

SOURCE

Credit Line

Gift of Dunlop Perdrian Rubber Co Ltd, 1934

Acquisition Date

26 July 1934

Copyright for the above image is held by the Powerhouse and may be subject to third-party copyright restrictions. Please submit an Image Licensing Enquiry for information regarding reproduction, copyright and fees. Text is released under Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivative licence.

Image Licensing Enquiry

Object Enquiry