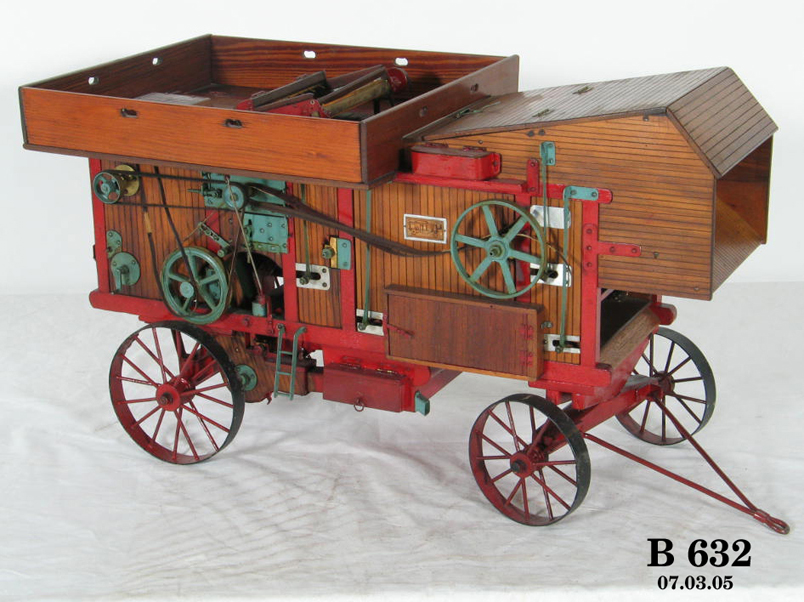

Model of Ransome's threshing machine made in 1931

Object No. B632

This is a model of a Ransomes' threshing (or thrashing) machine representing a machine made in England by Ransomes Sims & Jefferies Ltd of Ipswich, Suffolk. Ransome's threshing machine was in common use for threshing wheat in Britain, Australia and some other countries. Made in 1931 by H. Rand of Berwick-upon-Tweed, England, this model was purchased by the Museum in 1939. After a crop was harvested with a reaper binder and bundled into sheaves, these machines were pulled to the field and powered by a steam portable engine, traction engine or tractor, to rapidly separate the grain from straw and chaff. This was in the era before combine harvesters, which cut out the bundling step and separated out the grain while on the move. While it required much less labour than the older method of winnowing by hand, it needed workers on the ground to throw sheaves up to workers stationed on top of the machine, who fed the material into it. Men standing on top of a threshing machine fed sheaves of grain crops such as wheat, oats, maize and barley down through a series of armed rollers, which beat the stalks and separated the grain from the straw. The grain was collected in sacks at one end and the stalks were moved to the other end of the machine on a conveyer belt that allowed extra grain to drop through and be caught. This English threshing machine, which was distinct in design from those made in America, threshed and cleaned around 12 to 24 bushels per hour. Debbie Rudder Threshing machines (also called thrashing machines, grain threshers and separators, ) separated cereal grains from stalks and the seedheads of plants. The universal design of threshing machines in use by the 1920s involved a rotating drum working against an adjustable concave that partially encircled it. The machine could be adapted to different kinds and conditions of crop by adjusting the concave to vary its clearance from the drum. There were two types of drum, the high-speed, rubbing or beater drum and the low-speed, peg-tooth drum. The high-speed drum usually had eight rolled-steel beater bars with ribbed faces and a concave with plain rectangular bars parallel with the beaters. The drum diameter varied from 20 inches (50.8 cm) to 24 inches (61 cm) and had a speed of about 1000 rpm to 1100 rpm. The majority of ordinary British machines were 4 feet 6 inches (1.4 m) wide which allowed most varieties of cereal to be fed through parallel with the beaters. Although narrower machines were available they were not fitted with a rotary screen. The peg-tooth drum was most commonly used in small Scotch threshers and on American threshers of all sizes, and though it threshed very cleanly and had a low power requirement it broke the straw rather badly. The bars of the drum were not ribbed but were fitted with steel pegs which passed between similar pegs on the bars of the concave. The width of the drum varied from 18 inches (45.7 cm) to 44 inches (117.8 cm), 27 inches (68.6 cm) to 36 inches (91.4 cm) being the common size, and its speed was at least 700 rpm. A 36 inch (91.4 cm) machine required a 15 hp or 16 hp portable steam engine or traction engine, though smaller sizes were generally powered by horses or portable ail engines. Threshing machines were not only classified according to drum type but also according to their ability to clean and dress the grain, in that simple machines merely threshed the grain without dressing it, while finishing machines dressed the grain so that it could be marketed or even sown without passing through a winnower. These machines were also described as single-blast or first dressers and double-blast or second dressers. British finishing threshers were nearly always fitted with the high-speed drum and the separation of the cavings (small pieces of straw) and chaff was on the lines of the standard machine. The first dressing apparatus, for removing chaff and refuse, could act by suction or blast. Machines with a second dressing capacity had an elevator, a second fan, and a second series of riddles (sieves) at the engine end of the machine. While the first dressing machine delivered the grain in one quality the second dressing machine delivered it in two qualities. The essential difference between the second dresser and the finisher was the rotary screen. Threshing machines were eventually replaced in the mid 20th century by the combine harvester which both harvested and threshed the crop in the one operation. Despite this threshing machines continued to be made in Scotland into the 1960s. Margaret Simpson, Curator October 2018

Loading...

Summary

Object Statement

Ransome's threshing machine model, representing farm equipment made in England by the agricultural machinery manufacturers Ransomes Sims & Jefferies Ltd of Ipswich, Suffolk, England, these machines separated cereal grains from stalks and the seed heads of plants, wood / metal, made by H Rand, Tweedmouth, Berwick-upon-Tweed, Northumberland, England, 1931, part of A.A. Stewart Collection of model engineering

Physical Description

Ransome's threshing machine model, representing farm equipment made in England by the agricultural machinery manufacturers Ransomes Sims & Jefferies Ltd of Ipswich, Suffolk, England, these machines separated cereal grains from stalks and the seed heads of plants, wood / metal, made by H Rand, Tweedmouth, Berwick-upon-Tweed, Northumberland, England, 1931, part of A.A. Stewart Collection of model engineering The model is made of wood with metal wheels.

DIMENSIONS

Height

370 mm

Width

305 mm

Depth

660 mm

PRODUCTION

Notes

The model was made by H Rand of Tweedmouth, Berwick-upon-Tweed, Northumberland, England, in 1931. Threshing machines (also called thrashing machines, grain threshers and separators, ) separated cereal grains from stalks and the seedheads of plants. The universal design of threshing machines in use by the 1920s involved a rotating drum working against an adjustable concave that partially encircled it. The machine could be adapted to different kinds and conditions of crop by adjusting the concave to vary its clearance from the drum. There were two types of drum, the high-speed, rubbing or beater drum and the low-speed, peg-tooth drum. The high-speed drum usually had eight rolled-steel beater bars with ribbed faces and a concave with plain rectangular bars parallel with the beaters. The drum diameter varied from 20 inches (50.8 cm) to 24 inches (61 cm) and had a speed of about 1000 rpm to 1100 rpm. The majority of ordinary British machines were 4 feet 6 inches (1.4 m) wide which allowed most varieties of cereal to be fed through parallel with the beaters. Although narrower machines were available they were not fitted with a rotary screen. The peg-tooth drum was most commonly used in small Scotch threshers and on American threshers of all sizes, and though it threshed very cleanly and had a low power requirement it broke the straw rather badly. The bars of the drum were not ribbed but were fitted with steel pegs which passed between similar pegs on the bars of the concave. The width of the drum varied from 18 inches (45.7 cm) to 44 inches (117.8 cm), 27 inches (68.6 cm) to 36 inches (91.4 cm) being the common size, and its speed was at least 700 rpm. A 36 inch (91.4 cm) machine required a 15 hp or 16 hp portable steam engine or traction engine, though smaller sizes were generally powered by horses or portable ail engines. Threshing machines were not only classified according to drum type but also according to their ability to clean and dress the grain, in that simple machines merely threshed the grain without dressing it, while finishing machines dressed the grain so that it could be marketed or even sown without passing through a winnower. These machines were also described as single-blast or first dressers and double-blast or second dressers. British finishing threshers were nearly always fitted with the high-speed drum and the separation of the cavings (small pieces of straw) and chaff was on the lines of the standard machine. The first dressing apparatus, for removing chaff and refuse, could act by suction or blast. Machines with a second dressing capacity had an elevator, a second fan, and a second series of riddles (sieves) at the engine end of the machine. While the first dressing machine delivered the grain in one quality the second dressing machine delivered it in two qualities. The essential difference between the second dresser and the finisher was the rotary screen. Threshing machines were eventually replaced in the mid 20th century by the combine harvester which both harvested and threshed the crop in the one operation. Despite this threshing machines continued to be made in Scotland into the 1960s. Simpson, Margaret & Phillip, 'Old Farm Machinery in Australia', Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst, NSW, 1991 The threshing machine represents those made by Ransomes Sims & Jefferies Ltd of Ipswich, Suffolk, England. The firm was established in 1785 by Robert Ransome as Ransome & Co. from 1785 to 1809, became Ransome & Son from 1809 to 1818; Ransome & Sons from 1818 to 1825; James & Robert Ransome from 1825 to 1829; J.R. & A. Ransome in 1829-1830; and Ransomes & May from 1830 to 1846, after Charles May of Ampthill, Bedfordshire, joined the firm. The firm were the first to build steam portable engines in 1841 but with a vertical boiler. May left the firm to form Brown & May. Ransomes then became Ransomes & Sims from 1846 to 1852; Ransomes, Sims & Head from 1852 to 1881; Ransomes, Head & Jefferies from 1881 to 1884; and Ransomes, Sims & Jefferies Ltd from 1884. They sold the steam engine part of the business to Robey & Co. in 1956. The agricultural side of business was sold to Electrolux in 1989, then the American mower manufacturer, Jacobsen, in 1997.

HISTORY

Notes

This model is a part of the A. A. Stewart collection of ship, mechanical, and railway models acquired by the Powerhouse Museum between 1938 to 1963. Albyn A. Stewart was a trained engineer fascinated by engineering models and he constructed some of those in the collection. Others however were brought from amateur and commercial modellers at great expense to Stewart who travelled regularly to England to seek out models. In January 1938, Percival Marshall, the editor of 'The Model Engineer', England's premier modelling magazine, devoted editorial space to the collection where he stated that "Mr. Stewart has been fortunate in acquiring some excellent examples of both screw and paddle marine engines of considerable value as records of real prototype practice." In April of the same years he expanded his comments on the collection by saying, "As a trained engineer himself, his judgement of the technical merits of a model is very sound, and I should imagine that his collection is now the finest of its kind in Australia, in private hands. Many of the models are undoubtedly worthy of careful preservation, and I hope that they will eventually find a suitable resting place in one or other of the Australian national museums." Stewart was first contacted by the Technological Museum, as the Powerhouse Museum was then known, in 1933. The then Director/Curator A. R. Penfold immediately recognised the importance of the engineering models and in 1935 began to borrow items for display. Penfold expanded the area available for displaying the models as they were seen to be as instructive for students at the adjacent Technical College as they were for the general public. In early 1938 Stewart's company Lymdale Ltd, which owned most of the models, was approached about the purchase of a large part of the collection. Stewart was appointed to the Advisory Board of the Museum and in July 1938 it began to purchase the models it had borrowed as well as the best examples in the rest of the collection. The cost of this was estimated at over 3000 pounds. By 1943 the museum was still acquiring material from the collection and the Advisory Committee made a special appropriation request to the Minister of Education. "In view of the advantage of retaining a collection intact, and the national asset which the museum possesses, the committee recommends the purchase of the remainder of the Stewart collection offered at approximately 2,400." This sum was approved and between 1943 and 1945 around 80 more models were purchased. Apart from the monetary limitations the acquisition was spread over a number of years because some of Stewart's models needed to be finished before they could be sold. The high costs reflected the quality of the models. Many of the working steam engines are one-off examples hand crafted by amateur modellers over the course of years. The same is true of some of the ship and locomotive models, many of which are made to exact scale and include working parts. The models were carefully selected by Stewart who collected as much for posterity as he did for personal interest. Once contacted by the museum, he deliberately sought models which would fill historical and technological gaps and as a result the collection is one of the most significant still extant in Australia. A. A. Stewart died in 1961. Geoff Barker, March, 2007 References Marshall, Percival, 'The Model Engineer and Practical Electrician', London, April 29, 1937 Marshall, Percival, 'The Model Engineer and Practical Electrician', London, May, 27, 1937 Marshall, Percival, 'The Model Engineer and Practical Electrician', London, January, 27, 1938 Marshall, Percival, 'The Model Engineer and Practical Electrician', London, April, 14, 1938 Chalmers, A. Mar, 'The Model Engineer in Australia and New Zealand, Melbourne', January, 1939 Davison, G., Webber, K., 'Yesterday's Tomorrows: the Powerhouse Museum and its precursors 1880-2005', Powerhouse Publishing, 2005 Lavery, B. and Stephens, S., 'Ship Models; their purpose and development from 1650 to the present', Zwemmer, London, 1995

SOURCE

Credit Line

Purchased 1939

Acquisition Date

1 August 1939

Copyright for the above image is held by the Powerhouse and may be subject to third-party copyright restrictions. Please submit an Image Licensing Enquiry for information regarding reproduction, copyright and fees. Text is released under Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivative licence.

Image Licensing Enquiry

Object Enquiry