Engine and test rig for flying machine

Object No. B1429

The Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences holds the largest collection of material internationally of the aviation pioneer, Lawrence Hargrave. While no single individual can be attributed to the invention of the aeroplane, Hargrave belonged to an elite body of scientists and researchers (along with Octave Chanute, Otto Lilienthal and Percy Sinclair Pilcher) whose experiments and inventions paved the way for the first powered, controlled flight achieved by the Wright Brothers on December 17, 1903. Hargrave's greatest contribution to aeronautics was the invention of the box or cellular kite. This kite evolved in four stages from a simple cylinder kite made of heavy paper to a double-celled one capable of lifting Hargrave sixteen feet off the ground. The fourth kite of the series, produced by the end of 1893, provided a stable supporting and structural surface that satisfied the correct area to weight ratio which became the foundation for early European built aircraft. For example, Hargrave's box kite appears to be the inspiration for Alberto Santos Dumont's aircraft named '14bis', which undertook the first powered, controlled flight in Europe in 1906. Similarly, Gabriel Voisin states in his autobiography that he and his brother Charles, who manufactured the first commercially available aircraft in Europe, owe their inspiration to their construction to a Hargrave box kite, while via correspondence with Octave Chanute, there is also evidence for Hargrave's box kite influencing the aircraft used by the Wright Brothers during their historic flight in 1903. Hargrave's contribution to aeronautics can also be observed in other ways. For example, he conducted important research into animal movement and produced a number of flapping models which successfully demonstrated a means of propulsion. However, the flapping wing models were unable to ascend or lift from ground level with manpower alone. This prompted Hargrave to design and produce alternative power sources including a variety of engines, the most influential being his three cylinder radial rotary engine. This arguably formed the basis of the idea for the famous French Gnome engine, which became the primary source of aircraft power for the French Allies in World War I. Beyond aviation, Hargrave is also significant for his exploration work in the Torres Strait and New Guinea. In 1876, for example, he joined Luigi d'Albertis' expedition to the Fly River and on completion, was regarded as an expert cartographer who held an unrivalled knowledge of the region. Hargrave also contributed to the study of astronomy with his development of adding machines to assist Sydney Observatory in their calculations. He similarly researched and wrote on Australian history and was an early proponent for the establishment of a bridge across Sydney Harbour. References Adams, M., "Wind Beneath His Wings - Lawrence Hargrave at Stanwell Park" (September 2004) ADB Online, "Lawrence Hargrave", http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A090194b.htm (Downloaded 18/7/2007) Grainger, E., "Hargrave and Son - A Biography of John Fletcher Hargrave and his son Lawrence Hargrave" (Brisbane, 1978) Hudson Shaw, W & Ruhen, O., "Lawrence Hargrave - Explorer, Inventor & Aviation Experimenter" (Sydney, 1977) Roughley, T.C., "The Aeronautical Work of Lawrence Hargrave" (Technological Museum, Sydney Bulletin No.19, 1939)

Loading...

Summary

Object Statement

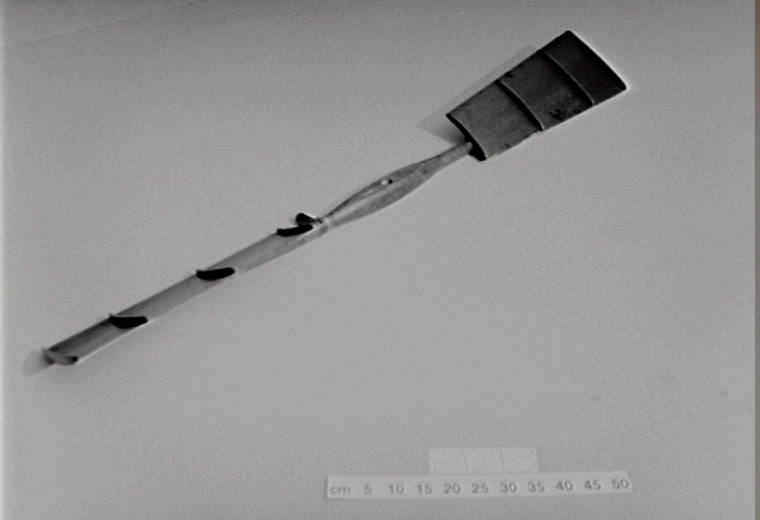

Model, four cylinder petrol engine, frame and propeller, No 27, metal / wood / wire / string, made by Lawrence Hargrave, Woollahra Point, New South Wales, Australia, 1900

Physical Description

Model engine for a flying machine with other components for testing. Parts include: Triangular wooden frame with fitted wooden seat. Four cylinder vertical screw engine with pistons coupled by means of a crosshead or scotch-crank. The crank is cuffed to screw and the blades of the propeller are tapered from outer tip. Automatic inlet - cam - operated valves and brass gears with hit and miss style linkage. The engine was originally mounted on the triangular frame with wooden seat. Now mounted on a museum made metal stand which has been painted black. Propeller made of dark stained wood featuring a slightly tapered sail that is ribbed on one side. Bolt, washer and pin made of metal. See P2903-11/14 and P2903-9/183 for a photograph of this engine

PRODUCTION

Notes

This four cylinder petrol engine and its components was designed and made by Lawrence Hargrave at Woollahra Point, New South Wales, Australia in 1900. Prior to the engine's construction, Hargrave estimated in his papers that it would weigh only 11 lbs; deliver five horsepower at 600 rpm with a sufficient safety factor and drive a two-bladed propeller. He also intended for the assembly and pilot to be located on a tubular metal frame suspended from ten or twelve cellular kites, which would have 250 square feet of supporting surface. However, these initial plans for the engine did not resonate. The final weight of the engine was 15 lbs and it was found to deliver five horsepower at only 500 rpm.

HISTORY

Notes

In mid 1887, Hargrave began to concern himself with forms of motive power (after his experimentation with India rubber powered models), making contact with the London engineers H.V. Ahrbecker, Son & Hawkins for details of engines available for aviation purposes and Major Penrose of the Royal Engineers in Sydney for details of the Brotherhood three cylinder radial compressed air engine which powered the Whitehead torpedo. This inspired Hargrave from the first half of 1888, to commence work on the design and construction of his own engines for flying machines. The first type he produced was single cylinder compressed air motors which were used to drive two flappers (in his flapping wing machine models). After finding this type of engine to be unsatisfactory, however, Hargrave began work on a second engine powered by petrol vapourised in a second boiler, before producing his more successful three cylinder radial rotary engine. This particular engine model was one of the first four cylinder internal combustion engines to be made and the only four cylinder engine to be built by Hargrave (he also designed, but did not build, a further three). The engine was tested on September 18, 1900 but was reported to have been of faulty design. A consultant engineer, M. T. Nelmes Bluck identified these faults as follows: (1) Solid pistons were used in place of a pair of overlapping rings in each piston (2) A larger pipe was needed from the carburettor with a fine adjustment on the extra air duct (3) The eight valve springs outside the cylinders needed replacement and, (4) Heat radiators or fins were needed on the cylinder housing These faults meant there was no allowance for heat to be generated. In response to the recommendations made by Nelmes, Hargrave wrote in a letter to C. F. Hitchins in London, "I have just had a bad knock in discovering some radical defects in my first attempt at a four-cylinder engine…this means twelve months work to do over again". However, it seems Hargrave's thinking into the four cylinder engine was lagging compared to other experimenters of the time. Hudson Shaw remarks that he was "aiming too high, planning for a bare weight of 15 lb for a power output of five horsepower" when "the power/weight ratio of the best engines - and later, of Weight's successful engines - was almost 11 lb a horsepower delivered". This model was donated to the MAAS by the Deutsches Museum in Munich, Germany in 1961. In 1901, Hargrave began approaching collecting institutions (including the Technological Museum in Sydney, the University of Sydney, the Royal Aeronautical Society in London, the Science Museum in London and the Smithsonian Institute in Washington) to see if they would house his models. However, because Hargrave only offered his models with the proviso that they were to be displayed altogether in glass cases from the moment of acquisition, none of the institutions accepted his offer. In 1910, Hargrave donated all but a few of his models to the Deutsches Museum at the instigation of Lieutenant Colonel Moedebeck of Germany. This action sparked considerable outrage, as space in the Technological Museum had been offered by the State Government to house the models. Although the newly opened Museum provided the models with a display area and an appropriate level of conservation care, they were not to escape the destruction of the Allied bombing of Munich during WWII. Fifty-seven models were destroyed out of a total of eighty. This prompted Stanley Brogden, who was responsible for inspecting the models at the time, to recommend that the Director of the Technological Museum in Sydney contact the Deutsches Museum advocating for their return. In 1960, this was made successful, and in the following year, nineteen objects were handed over to the MAAS. Four were temporarily withheld by the Deutsches Museum until copies were made and the originals returned to Sydney a short time later. The second of four children of John Fletcher and Ann, Lawrence Hargrave was born at Greenwich, London on January 29, 1850. In 1856, Lawrence's father, eldest brother Ralph and uncle Edward emigrated to Australia in what appears to be a consensual marital separation between John and Ann. They were bound for Sydney to join a third brother of John and Edward, who was a member of the Legislative Assembly for New England (named Richard), while Ann, Lawrence and her two other children, Alice and Gilbert, stayed in Kent, England. During his early years, Lawrence was educated at the Queen Elizabeth's School in Kirkby Lonsdale, Westmoreland, before he sailed to Australia in 1865 to join his father, brother and two uncles. John Fletcher, who was a distinguished judge in the New South Wales Supreme Court living at Rushcutters Bay House, anticipated a career for Lawrence in law. Despite organising tuition for him, Lawrence failed to matriculate, but was subsequently accepted to begin an apprenticeship with the Australasian Steam Navigation Company (ASN Co) in 1867. For five years he worked as an apprentice, gaining invaluable skills in woodworking, metalworking and design. The circumnavigation voyage of Australia aboard the 'Ellesmere' (offered to Lawrence by another passenger en route to Australia from London) obviously stimulated an interest for Lawrence in exploration. From 1871, Lawrence joined the Committee of Management of J.D. Lang's New Guinea Prospecting Association and in 1872 was on board the brig 'Maria', bound for New Guinea in search of gold, when it sunk off Bramble reef, north Queensland, causing great loss of life. After returning to Sydney to work for the ASN Co, and later the engineers P.N. Russell & Co, Lawrence participated in several more exploratory voyages to the Torres Strait and New Guinea, accompanying figures like William Macleay, Octavius Stone and Luigi d'Albertis along the Fly River. These voyages continued until 1876, at which time Lawrence worked at the foundries of Chapman & Co, before choosing to settle down with new wife, Margaret Preston Johnson in September, 1878 with whom he had six children (Helen-Ann (Nellie), Hilda, Margaret, Brenda, Geoffrey and Brenda-Olive). In January of the following year, Lawrence commenced work as an extra observer (astronomical) at Sydney Observatory under the Government astronomer H.C. Russell. In this role, Lawrence was able to make a number of important observations and inventions, including the transit of Mercury in 1881, the Krakatoa explosion in 1883 and the design and construction of adding machines. The income made from land bestowed to Lawrence by his father in Coalcliff, however, meant that in 1883 Lawrence was able to resign from his position at the Observatory to pursue his fascination and study into artificial flight. This interest came about from his observation of waves and animal motion, including fish, birds and snakes. Lawrence's earliest experiments, spanning 1884-1892, involved propulsion with monoplane models built from light wood and paper. He first attempted to build a full-size machine capable of carrying a human in 1887 and in 1889 he built his most influential engine - a three cylinder radial rotary engine. Lawrence's later experimental phase, 1892-1909, involved the use of curved surfaces in his models. This research subsequently led to the development of the box kite, the most famous invention associated with his name. Lawrence always conducted his experiments in his local area (i.e. Rushcutters Bay, Woollahra Point and Stanwell Park). He was against patenting his inventions for fear of stifling the development of aviation in the bigger picture and therefore published his results quickly and widely, particularly through the Royal Society of New South Wales. This Society helped Lawrence to gain an international reputation and brought him into contact with other aviation pioneers like Octave Chanute and Otto Lilienthal. The very first paper he gave was "The Trochoided Plane" (delivered August 6, 1884). In Lawrence's later years he conducted research into early Australian history, postulating the theory that two Spanish ships found their way into Sydney Harbour in the late 16th century. Apart from this and of course his interests in aeronautics, Lawrence also concerned himself with the contemporary issues of patent laws, free competition, Darwinism, a bridge for Sydney Harbour, pensions, strikes and conscription. Lawrence Hargrave died of peritonitis at Lister Hospital on July 6, 1915. Lawrence's death came only nine weeks after the death of his youngest son, Geoffrey, at Gallipoli.

SOURCE

Credit Line

Gift of the Deutsches Museum, 1961

Acquisition Date

23 January 1961

Copyright for the above image is held by the Powerhouse and may be subject to third-party copyright restrictions. Please submit an Image Licensing Enquiry for information regarding reproduction, copyright and fees. Text is released under Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivative licence.

Image Licensing Enquiry

Object Enquiry