Ushabtis figure

Object No. A4668

Egyptian ushabtis, also commonly referred to as shawabti or shabtis (meaning "answerer"), are funerary figurines, usually mummiform in shape, which were buried with the deceased in their tomb. The purpose of ushabtis was to perform the laborious tasks required for the production of food for their owners in the afterlife (such as sowing seeds, harvesting crops and irrigating the land). Ushabtis were used by both royal and non-royal Egyptians. This ushabtis provides a representative example for the types of mass-produced ushabtis produced during the pinnacle of their consumption during the Third Intermediate Period. Compared to many earlier examples, it is of a high quality with well-defined details and traces of hieroglyphic text. Ushabtis are one example of the type of objects that the deceased had buried with them in their tombs. Other objects included food offerings, canopic jars and pottery vessels, which obviously varied depending on the social standing of the tomb owner. From the New Kingdom onwards, some tomb owners were buried with shabtis boxes which contained 365 worker shabtis and 36 overseer shabtis. This faience worker shabtis is an indicative example for the funerary beliefs held by the Ancient Egyptians. It reinforces the idea that the Egyptians believed eternal life could be ensured through the provision of statuary equipment, along with other means, and that the physical world was a chance to prepare for the next life. Researched by Melanie Pitkin References Birrell, M., "Ushabtis in the Macquarie University Ancient History Teaching Collection", Bulletin of the Australian Centre for Egyptology, vol 2 (Sydney, 1991) Janes, G., "Shabtis: A Private View" (Cybele, 2002) Kaczmarczyk, A., "Ancient Egyptian Faience: an analytical survey of Egyptian faience from Predynastic to Roman times" Kanawati, N., "The tomb and its significance in Ancient Egypt" (Giza, 1987) Kitchen, K., "The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt" (Warminster, 1973) Nicholson, P., "Egyptian Faience and Glass" (Buckinghamshire, 1993) Petrie, W.M.F., "Shabtis" (London, 1935) Schneider, H. D., "Shabtis" vols. 1-3 (Leiden, 1977) Ranke, H., "Die Agyptischen Personannamen" vols. 1-2 (Holstein, 1935) Shaw, I & Nicholson, P., "The British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt" (Cairo, 2002) Stewart, H., "Egyptian shabtis" (Buckinghamshire, 1995)

Loading...

Summary

Object Statement

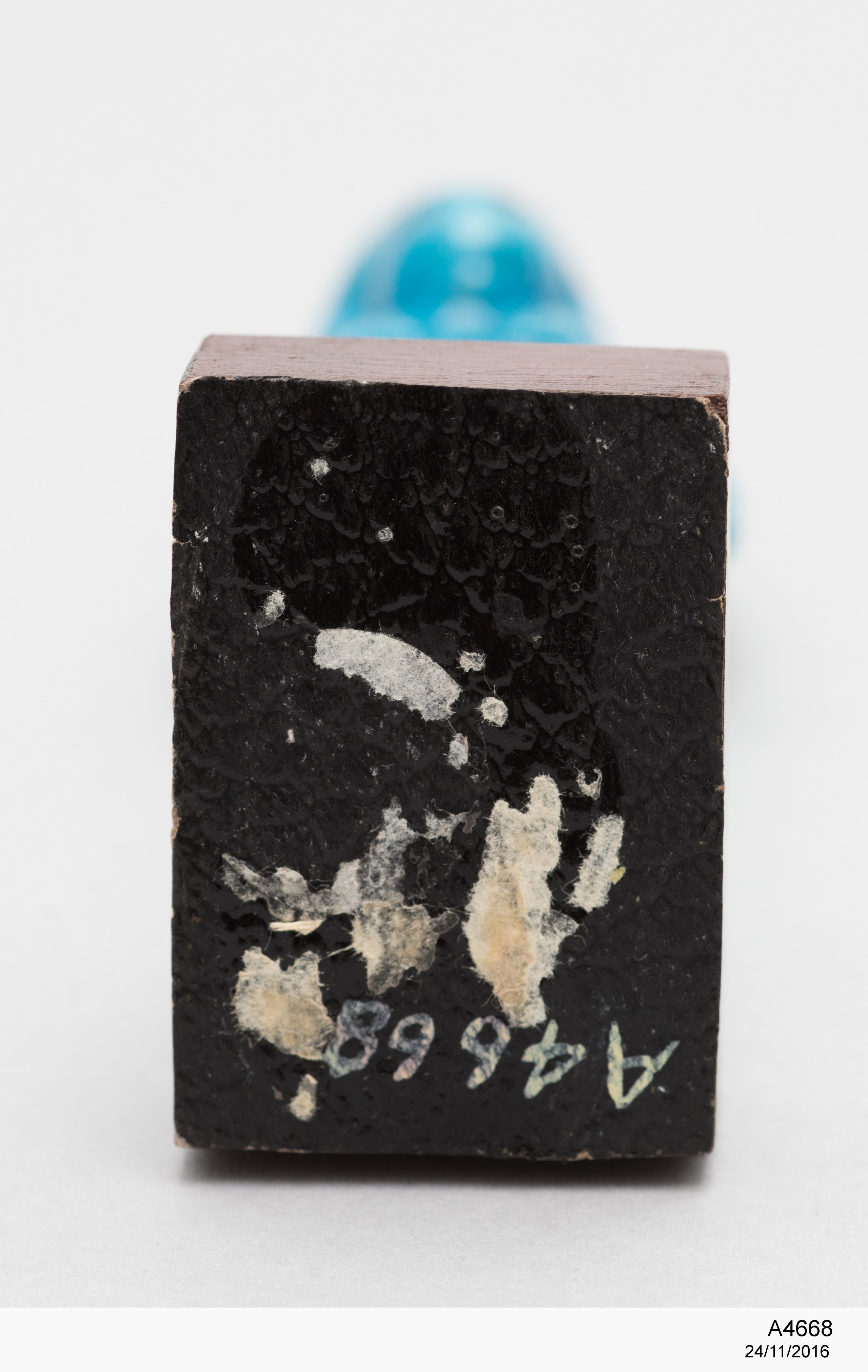

Worker ushabtis figure, named Djed-khonsu-iwf-ankh, the 'Overseer of Granaries', Egyptian faience, Deir el-Bahri, Egypt, Dynasty 21, Third Intermediate Period (1080-945 BC)

Physical Description

Male mummiform figure made of Egyptian faience with an exterior cobalt blue glaze and mounted on a square wooden base. The figure is shown wearing a headdress and 'seshed' headband knotted at the back. The body is wrapped in bandages with only the head and arms visible, which are crossed over at the chest. Black hand painted decoration has been used to denote the eyes, headdress and headband, as well as two hoes held in each of the figure's hands and a vertical column of hieroglyphic text down the centre front of the body. There is also a black painted seed bag on the back.

DIMENSIONS

Height

125 mm

Width

38 mm

Depth

47 mm

PRODUCTION

Notes

This ushabtis is made from Egyptian faience and dates to Dynasty 21 (1080-945 BC). It was produced for a deceased man named "Djed-khonsu-iwf-ankh" (whose tomb was excavated by Herbert Winlock at Deir el-Bahri). This name appears on other similar shabtis in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (E.9.1946 and E.10.1946), Kazan (15701), Lisbon (MNA E 99), Manchester, Moscow, New York (MMA 10.130.1063 a-d and 26.32.3), Toulouse and Winterthur (6780 (429)). Egyptian faience is a non-clay ceramic made up of quartz (obtained from sand, flint or crushed quartz pebbles), an alkali (such as plant ash or natron), lime and ground copper.These materials, when mixed with water, form a malleable paste which can be hand-modelled or moulded into various shapes and sizes. When fired, the quartz body develops a blue-green glassy surface, the characteristic attribute of faience, which the ancient Egyptians believed was symbolic of life, rebirth and immortality. While the processes of faience production are missing from the visual record, experimental archaeology has prompted Egyptologists to assert that four main stages were involved. This includes obtaining the high-quality materials; preparing the faience quartz paste; hand-forming or mould-making the object and then firing it in a kiln. It is likely that this work would have been undertaken by more than one person, presumably labourers, craftsmen and artisans and, most probably, in the same workshop where other goods, such as pottery and glass, were manufactured. After firing, the faience is glazed using one of three methods - efflorescence, cementation or application. Efflorescence is a self-glazing technique in which soluble salts are mixed with the raw quartz. During the drying stage, the salts migrate to the surface and when fired, they melt to become a glaze. Cementation is another self-glazing technique, where the object is submerged in glazing powder and upon firing, becomes fused to the surface. Application, on the other hand, involves immersing the object into a mixture of glazing powder or hand-painting. During the Third Intermediate Period, Egyptian ushabtis (such as this example) were mass produced from moulds. The black handpainted details were applied before the ushabtis was fired in a kiln at 800-1000 degrees temperature. Researched by Melanie Pitkin

HISTORY

Notes

Egyptian faience first appeared in the Late Predynastic period (3500BC) and was used all the way up until the Ptolemaic period (30BC). Although faience was used in many strata of society, it was essentially a luxury product and according to some, was initially developed as an inexpensive substitute for lapis-lazuli. The use of Egyptian faience in ushabtis did not occur until the Middle Kingdom. Prior to this, they were made from wood and developed out of the crude models of servants which were produced for tomb owners in the Old Kingdom. The purpose of ushabtis at this time was to represent the deceased owner and perform the laborious tasks for him of hunting and preparing food, irrigating the land and harvesting crops in the afterlife. Until the end of the Middle Kingdom, the deceased was normally buried with about 1-4 ushabtis and between 10 and 40 in the New Kingdom. By the Third Intermediate Period, the function of ushabtis changed. They were now divided into 'worker' ushabtis and 'overseer' ushabtis and most individuals were buried with up to 401 of them (365 'worker' ushabtis, one for everyday of the year and 36 'overseer' ushabtis who instructed the 'worker' ushabtis what to do). Thus, ushabtis were now being mass-produced and were perceived more as slaves of the deceased owner, rather than substitutes for them. Ushabtis lost their resonance for the Egyptian people during the Late Period and with the decline of the Osirian cult and gradual inability for people to write hieroglyphs in the Ptolemaic Period, they eventually disappeared altogether. This particular ushabtis was purchased by the Agent General for New South Wales from London on November 4, 1955. It is likely that the ushabtis originated from King Farouk's collection, which was auctioned by Sotheby's in the Palace Collections of Egypt sale (and administered from their London office) in 1954.

SOURCE

Credit Line

Purchased 1955

Acquisition Date

4 November 1955

Copyright for the above image is held by the Powerhouse and may be subject to third-party copyright restrictions. Please submit an Image Licensing Enquiry for information regarding reproduction, copyright and fees. Text is released under Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivative licence.

Image Licensing Enquiry

Object Enquiry