Letters from Ada Lovelace to Charles Babbage

Object No. 96/203/2

These letters are from Countess Ada Lovelace to Charles Babbage, an English mathematician, inventor, philosopher, and reformer who, more than 100 years before the computer age, designed a general-purpose mechanical calculating machine that anticipated the principles and structure of the digital computer. In 1823 Babbage started working on his Difference Engine No 1, a fully automatic machine that was designed to calculate and print the tables used in the burgeoning fields of science, navigation, and business. His aim was to relieve people of 'routine mental labour' and eliminate human error in calculations. The Difference Engine was designed to produce successive values of a polynomial function using the Method of Finite Differences. This method reduced the calculation to a series of additions. Once the initial values were entered into the machine, the operator would need only to turn the handle to generate the tables. Most significantly, the operator would not need to know any mathematics. Babbage worked on the Difference Engine No 1 for 11 years but was never able to complete it. There are a number of factors that contributed to his failure, including the strain and expense of having to develop new manufacturing machining techniques, personality clashes with his engineer, the death of his wife and several of his children and the general lack of understanding of his project. Babbage was perhaps also distracted by his conception for a more ambitious machine, the Analytical Engine, a machine capable of finding values for any algebraic function. Like the modern computer, it was to be a general purpose, programmable machine in which the storage of information was a separate function to the processing of information. The Analytical Engine was never built, and the ideas he developed had to wait another 100 years to be "rediscovered". While Babbage did not successfully complete any of his engines, his efforts had profound impact in other ways, particularly in the "mechanical arts" and on the organisation of manufacturing processes. Italian engineer Luigi Menabrea wrote a paper describing the workings of the analytical engine in 1842 after hearing Babbage lecture on his work in Turin. This article was translated from French to English by Ada Lovelace, the daughter of Lord Byron. She added lengthy notes to the original article in close consultation with Babbage, whom she greatly admired. Her paper contained detailed explanation of the significance of the engine and also a set of instructions to the machine for the generation of the Bernoulli series. This set of instruction is now regarded as the first computer program; while it is usually attributed to Ada Lovelace, it appears that she was probably instructed by Babbage. It is clear that she had a considerable mathematical ability and was referred to by Babbage as the 'Enchantress of Numbers'. Written by Erika Dicker Assistant Curator, 2007.

Loading...

Summary

Object Statement

Letters (2), from Countess Ada Lovelace to Charles Babbage, paper, England, 1838-1847

Physical Description

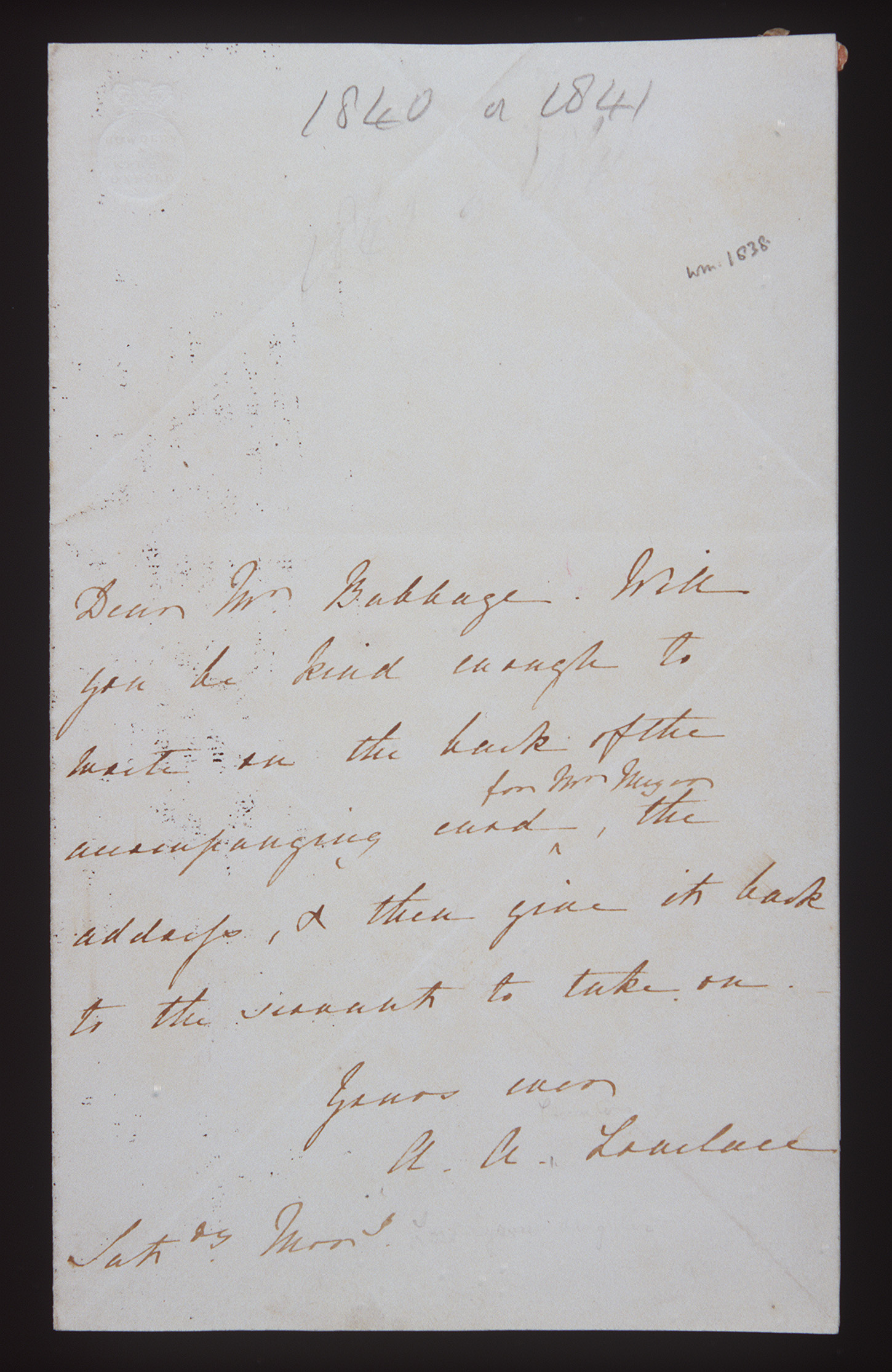

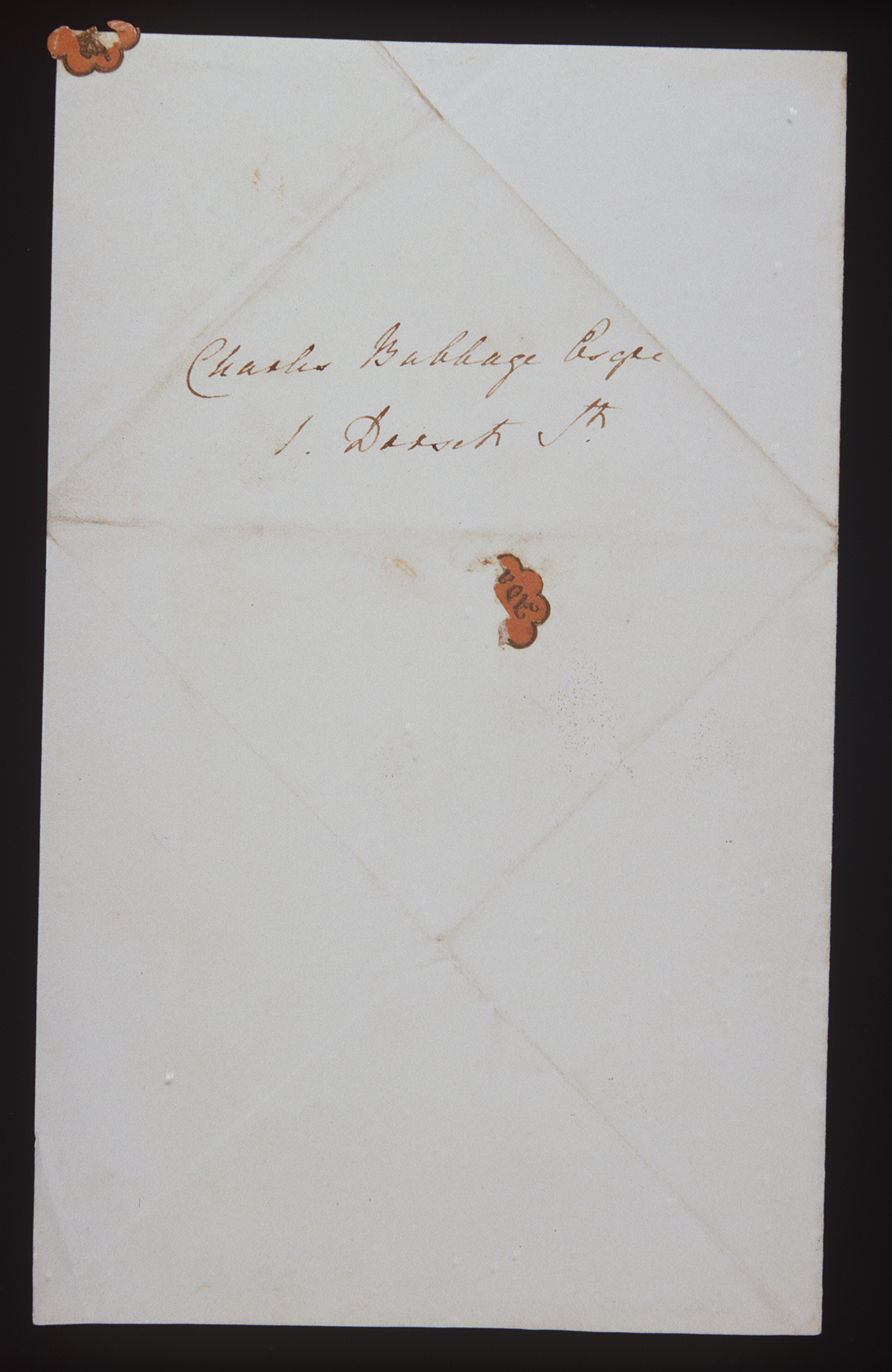

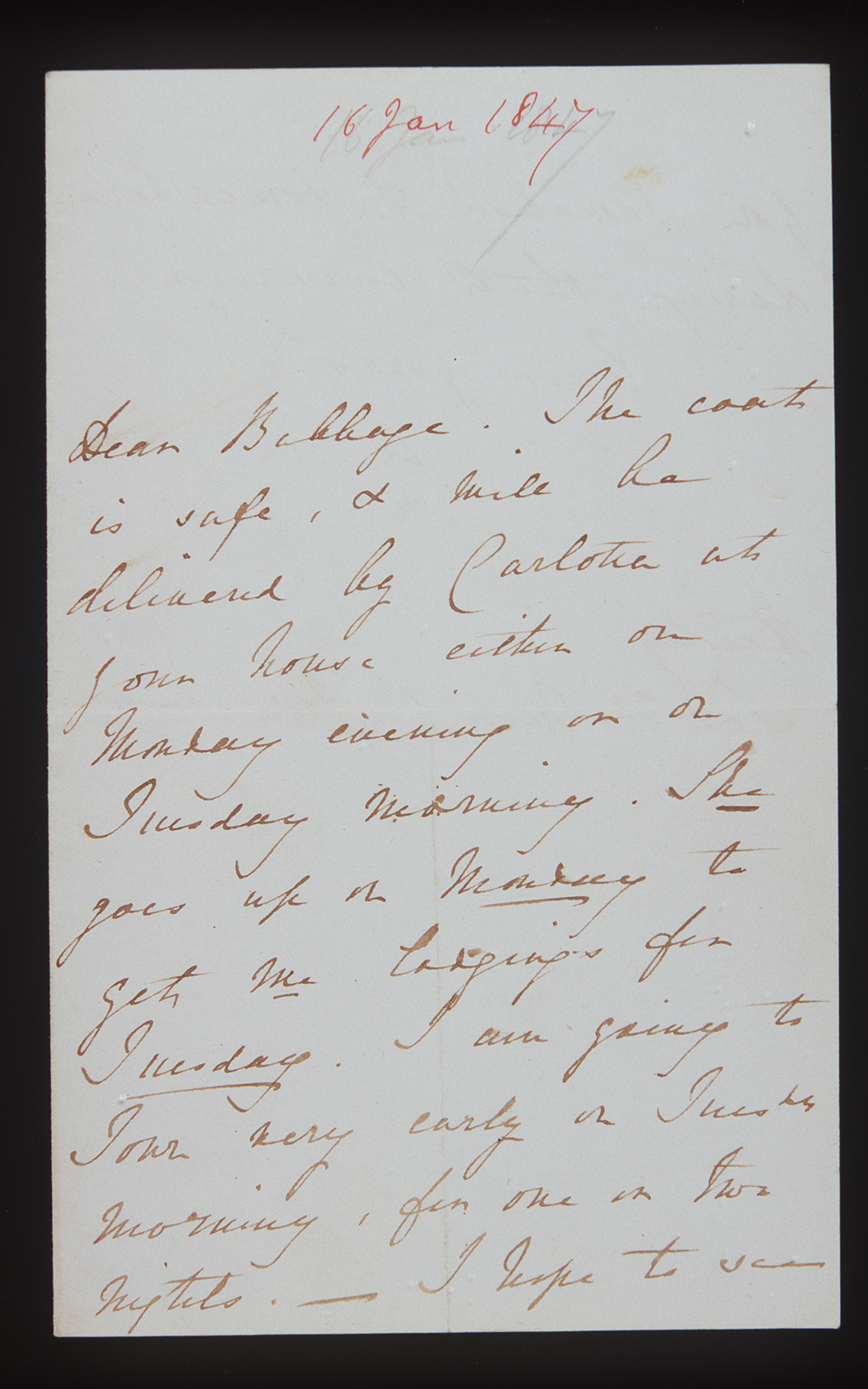

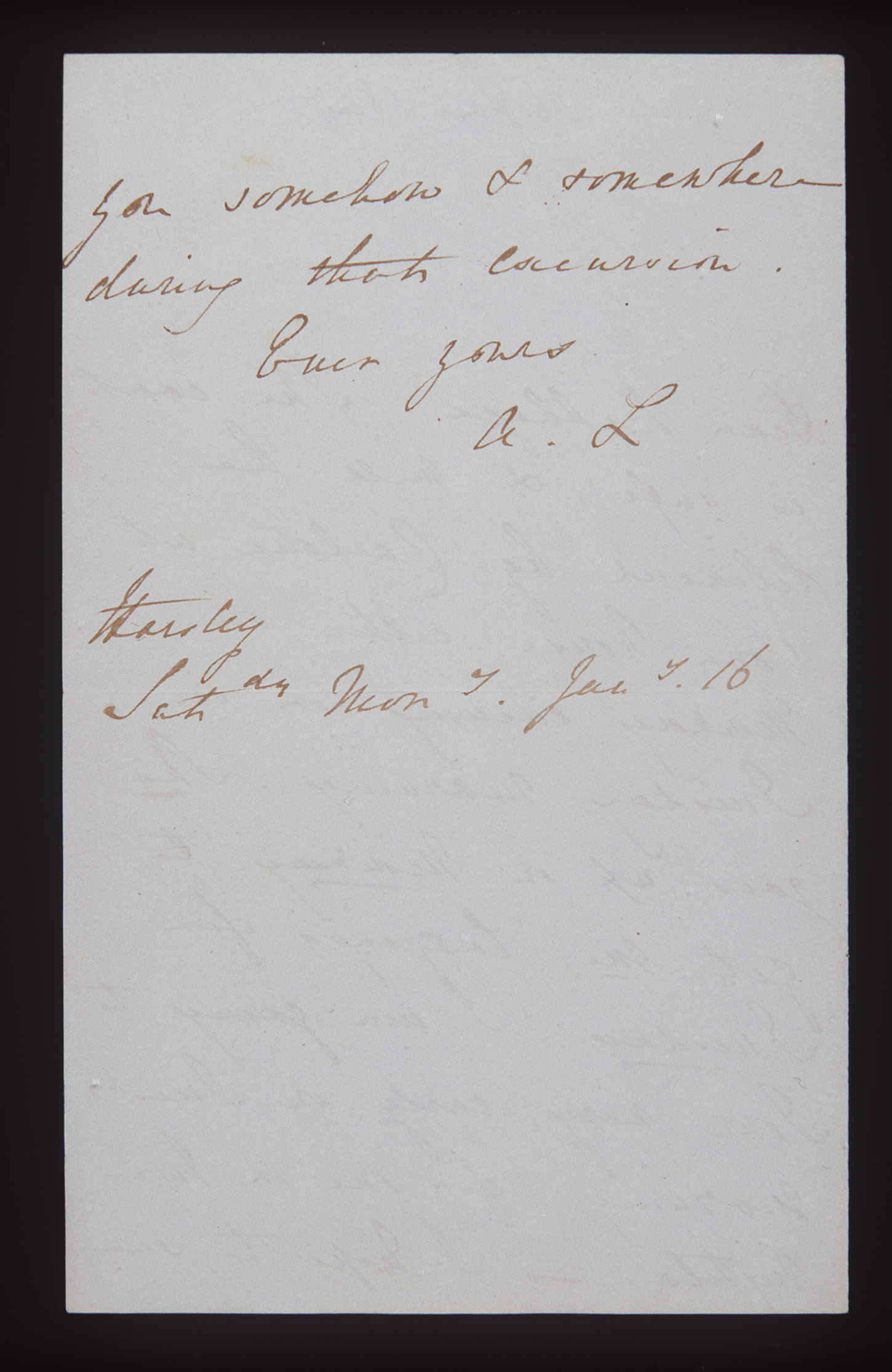

Two letters from Ada Lovelace, adressed to Charles Babbage, handwritten and folded into a self made envelope. The first is watermarked 1838 and attributed in later hand to 1840/41. It asks for an acquaintance's address and is addressed 'Dear Mr Babbage' and signed 'A A Lovelace'. The letter can be folded to create a small envelope, with two separate halves of the sticker or seal featured in orange with gold trim and a gold crown above 'Ada'. The second letter dated 1847 is addressed more familiarly as 'Dear Babbage' and signed 'A L'. This letter refers to the delivery of Mr Babbage's coat and an impending visit to London. This letter can also be folded to form an envelope, however no evidence of a seal.

DIMENSIONS

Height

185 mm

Width

225 mm

PRODUCTION

Notes

The letters are part of an acquisition that includes a specimen section of Charles Babbage's Difference Engine No 1. This calculating device was designed by Charles Babbage between 1822 and 1833, after which the project was abandoned. The mechanism demonstrated in the specimen was probably designed in the early stages. He designed the engine to automatically calculate and print mathematical tables, used at the time for complex calculations relating to navigation, surveying, astronomy, annuities etc. The engine was designed to use the Method of Finite Differences to generate successive values of a polynomial function. New tools and manufacturing techniques were developed to make it. Most of the parts were eventually made, but the machine was never assembled. While Babbage was working on the Difference Engine he started to think about a machine that would be more versatile. When the Difference engine project was abandoned he went on to design most of the Analytical Engine, which was in effect a programmable mechanical computer with the same architecture as a modern electronic computer. Certain innovations he developed for the Analytical Engine were later incorporated into a more efficient difference engine, Difference Engine No2. The parts for the Difference Engine were made by Joseph Clement who was a highly skilled toolmaker and tradesman. The unassembled parts of the Difference Engine were inherited by Henry Provost Babbage after the death of his father in 1871. In 1979 he assembled 5, 6 or 7 specimen pieces (accounts in the writings of Henry differ). These pieces were to demonstrate the addition and carry mechanism of the engine. One he gave to Cambridge, one to University College, London (now at the Science Museum), one to Harvard College in America, one to Charles Whitmore Babbage, Henry's nephew who took it to New Zealand. One, two or three others are unaccounted for.

HISTORY

Notes

These letters were purchased by the museum at auction along with a portion of Babbage's Difference Engine No 1. None of Babbage's machines was ever completed. But in 1832 he assembled a working portion to demonstate its function to the British Parliament in what was was probably a last attempt to gain continued funding. This portion, now at the Science Museum , was capable of generating, but not printing, tables for 2nd degree polynomials. Babbage did generate tables for some functions. The descendants offered the Engine and related material for auction through Christie's of London on 4 October 1995

SOURCE

Credit Line

Purchased 1996

Acquisition Date

6 June 1996

Copyright for the above image is held by the Powerhouse and may be subject to third-party copyright restrictions. Please submit an Image Licensing Enquiry for information regarding reproduction, copyright and fees. Text is released under Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivative licence.

Image Licensing Enquiry

Object Enquiry