Raffia currency mats made in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Object No. 89/762

These four (4) raffia currency mats are part of a collection of six textiles collected by May French-Sheldon in Zaire, Central Africa. They were made between 1880 and 1905 in Luobogh, Kassia, the Belgian Congo, by unknown makers of the Bakuba people of the Kuba region. They were collected by French- Sheldon during her expedition to the Belgian Congo from 1903 to 1905. The four rectangular pieces of plain weave cloth of raffia fibre were used as currency. The long sides of the cloths have short fringes, while the shorter ends have long fringes. Three are decorated with strips of narrow red, yellow and black ribbon, machined in place. In Kuba, creating textiles, such as raffia cloths, are a collaborative process. Men cultivate and weave the raffia, men and women decorate the cloths (although as will be seen some decoration was exclusively carried out by women), and both sew the cloths into garments. Raffia, from which is textile is made, grows in wetland areas. Raffia palm trees (Raphia ruffia) grow most prolifically in West Africa and Central Africa. This textile was produced in Zaire, in Central Africa. Raffia cloths have traditionally been produced in Zaire, although the production of raffia cloth has decreased since European cotton cloths were brought into Africa. To produce this cloth, the fibre was removed from young raffia leaves (only young leaves are used in this process). This was achieved by cutting the leaves, and then leaving them in the shade while enough leaves are collected. A sharp knife was then used to cut partially through the base of the leaves, so as not to cut the membrane, and the outer leaves were removed. The membrane was clear when removed, and only looked like yellow grass when it had dried out (hanks were laid in the sun to dry for approximately half a day, and turned regularly to avoid twisting). In preparation for weaving, the strands of raffia were split in half with fingers or, as is the case in some areas of Zaire, such as Kuba, with a fine comb. As was usual in Zaire, the strands would have then been arranged for weaving on the loom. This raffia mats were woven by men (in Zaire all weaving was and still is carried out by men), on a single-heddle loom. The raffia loom originated in the Congo area. The process of weaving raffia on this loom is different to the weaving of threads, which are tied to the loom on a continuous warp. When weaving raffia, the warp threads are tied to the top and bottom of the loom, thus making it a non-continuous warp. This can be done easily by slipping the raffia hanks onto two batons, which are then attached to the loom. Cloth has been used throughout Africa as a form of currency for centuries. As discussed by the Smithsonian Institution; "In Africa, where few extensive nation-states existed, commerce among various societies depended on commonly held values that spanned great geographical distances and a broad diversity of activities. Societies assigned worth to objects that were relevant to their own circumstances: objects that were rare enough to be valued yet plentiful enough to be widely traded. Daily monetary transactions were conducted with cowrie shells, aggrey (glass) beads, woven cloth strips, and raffia mats" (The Artistry of African Currency- National Museum of African Art). The "bamboo" or wine palm (rafia vinifera or ntombe) is most commonly used for the construction of raffia currency. The simplest piece of cloth used as currency is the libongo (or Mbongo). These were usually woven with a simple plain weave, the size of a large handkerchief, and could be sewn together to items on clothing, large cloths, etc. Currency was exchanged in Africa during significant lifetime events, such as births, becoming an adult, marriages and deaths, or simply as a peace offering. The value of the currency was based on the quality of the mats. Raffia currency was also used at markets to purchase food and other essential items, sewn together to make clothing, bags and floor and bed covers, and were also saved for future expenses. These raffia currency mats hold major significance due to their associations with Mary (more commonly known as May) French-Sheldon. They were collected during her second trip to Africa; an expedition to the Belgian Congo (now Zaire) between 1903 and 1905. Prior to her first 1891 expedition, May was a well travelled woman, but had never been to Africa. In 1891, at the age of 43, French-Sheldon went on a self-funded three month trek through the coast of East Africa, to the base of Mount Kilimanjaro, and back again. She claimed the title of "first woman explorer of Africa", although there are records of women travelling through Africa prior to French-Sheldon. However, she claimed the title because she was the believed herself to be the first woman to travel through Africa without a husband or European travel companion. May became well known after this trip, due to her displays of extravagance and self-importance. French-Sheldon had 150 African porters with her on the journey. She also had considerable luxuries on this journey. She travelled with an elaborate court dress, of white silk and satin, with silver trim, glass and paste jewels, along with a tiara, waist-length platinum blond wig, leather whip, hip pistols and a ceremonial sword. May wore this ensemble to meetings with important African men, including the sultan. This dress was from the well known House of Worth, and she often called herself, and became known as the "White Queen". For the times when she wasn't walking, French-Sheldon was carried by her porters in a comfortable palanquin, complete with silk cushions. She also had her complete china tea service with her during her travels. May French-Sheldon explored Africa at a time when men and women had rigidly defined roles, and the world was male dominated. As discussed by Boisseau, "French-Sheldon sought acclaim as an African explorer in an era when this seemed the epitome of adventurous masculine pursuits (Boisseau, Sultan to Sultan, p. 3). During the Victorian era, terms like "adventuress" and "exploratress" were viewed as "unusual novelties" (Boisseau, White Queen, p.201), and travelling without a chaperone was viewed as unthinkable and dangerous. French-Sheldon, however, wanted to be recognised equally alongside the great male explorers, who had returned from Africa, and had become influential because of their knowledge gained during their explorations. As described by Boisseau, she had a "desire for glory" (Boisseau, White Queen, p.107). Her desire to be widely known is evident from a passage she wrote in Sultan to Sultan; "Unwilling to travel among these natives without leaving some evidence of my presence, I had taken the precaution to have several thousand rings, on which were engraved my name, and to every native with whom I personally came into contact in the course of time I presented one of these souvenirs" (Sultan to Sultan, p. 123) She even referred to herself as "Bebe Bwana", which in Swahili means "Woman Man". Thus, she displayed both womanly and manly characteristics, and is considered to be one of the early feminists. French-Sheldon became a very popular public figure after her return in 1891, portrayed in the media as a successful explorer. In 1892, she published her book Sultan to Sultan: Adventures among the Masai and other Tribes of East Africa (by M. French-Sheldon, "Bebe Bwana"). As described in the Journalist during this time; "Mrs. French-Sheldon, the distinguished author and traveller, delivered one of the most vivid and entertaining lectures heard in the Metropolis for a long time. She gave a telling description of her expedition, and a lurid account of the manners and customs of the people. Mrs. Sheldon is of distinguished personality, far-seeing insight and magnetic presence. The interest she has awakened by her courageous explorations and brainy lectures is almost unprecedented ('Journalist', New York). By 1895, French-Sheldon's husband had died, leaving her financially unable to support her further hopes for travel. Her popularity had also subsided. In 1903, May was hired to act as an undercover spy in Congo by William E. Stead, co founder of the Congo Reform Association. This fourteen-month trip, unlike her previous expedition, was "shrouded in secrecy" (Boisseau, White Queen, p.108), and it was during this trip to Africa that these raffia currency mats were collected by French-Sheldon. As described by Boisseau, her task was to gain information on the; "conditions in the Congo Free State that would damage the reputation of King Leopold II of Belgium and help orchestrate the release of his military and economic grip on the region. However, unbeknownst to Stead and Morel, French-Sheldon's sympathies lay with the beleaguered Belgian King and her actions in the Free State and in Britain upon her return seem to have been those of a double agent (Boisseau, White Queen, p.11). When she returned to Britain, controversy was raised by her reports, as they were "at odds with other British voices on Africa…" (Boisseau, White Queen, p.108). After this time, in 1905-1907, French-Sheldon tried to establish a rubber plantation and colonisation company in Liberia, from knowledge she gained whilst in the Congo. Her company, the Americo-Liberian Industrial Company, failed. After her return to England, French-Sheldon once again became a very popular figure, having a particularly "profound effect on her young female audience in the 1920s" Boisseau, White Queen, p.182) with her public speaking. French-Sheldon, described in the St. Thomas newspaper as "one of the grandest women of the age", left a lasting impression on many during her lifetime and after. As encapsulated by the newspaper, The Carmel Pine Cone; "Hardly can we look now at the map of Africa without picturing [Madame French-Sheldon] that small dauntless figure, revolver in her belt, marching at the head of her mile-long line of natives across that land of mystery" (Carmel Pine Cone, February 16, 1924). On the label attached to this textile, it states that the raffia currency mats were from French-Sheldon's personal collection. Thus, they are of major historical importance due to their historical associations with French-Sheldon. They are also good representative examples of raffia currency mats, which have been traditionally important objects used in Africa as currency for hundreds of years. (Rebecca Fisher)

Loading...

Summary

Object Statement

Textile lengths (4), used as currency, raffia / textile, made by membrs of the Kuba, Congo Free State, 1880-1905

Physical Description

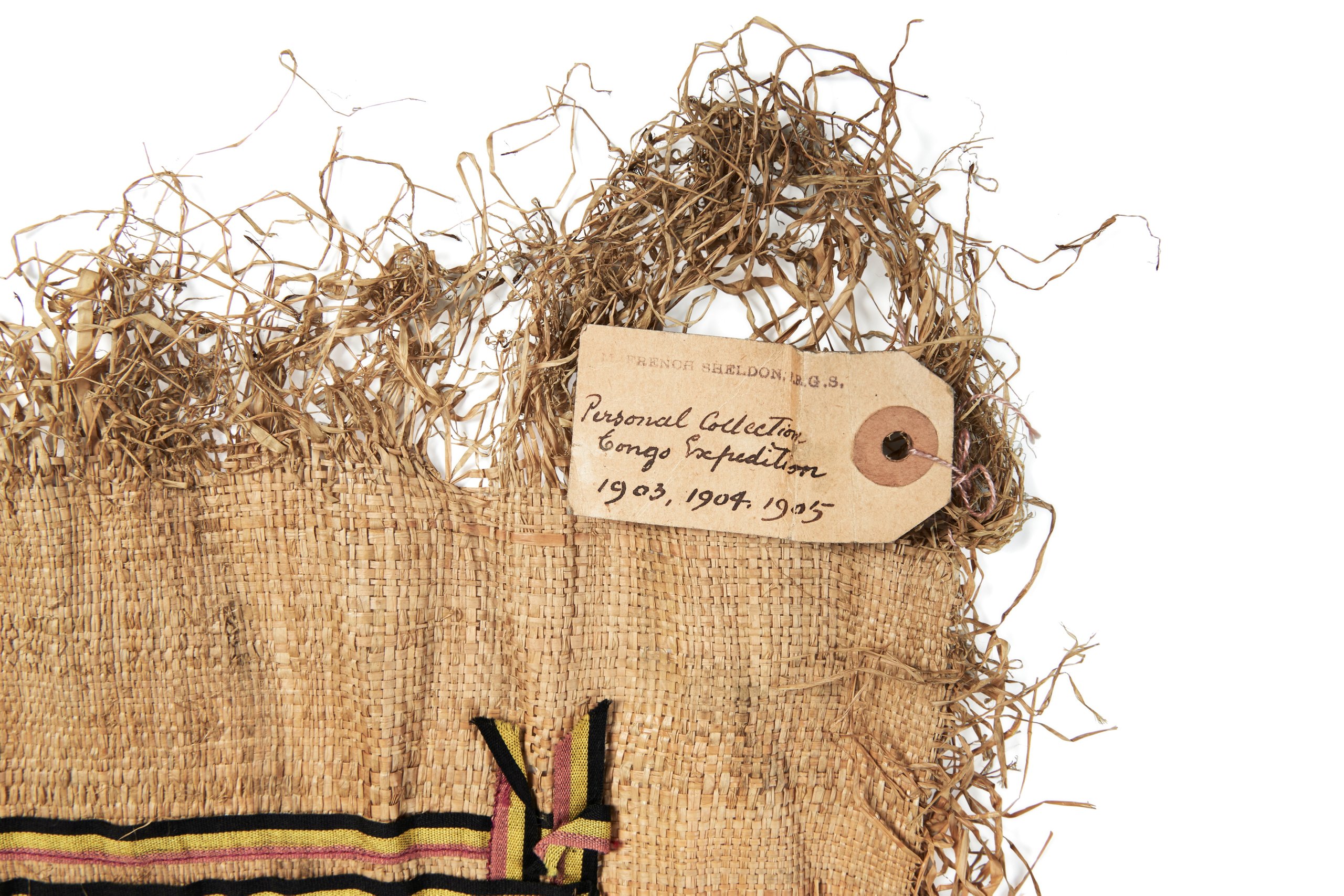

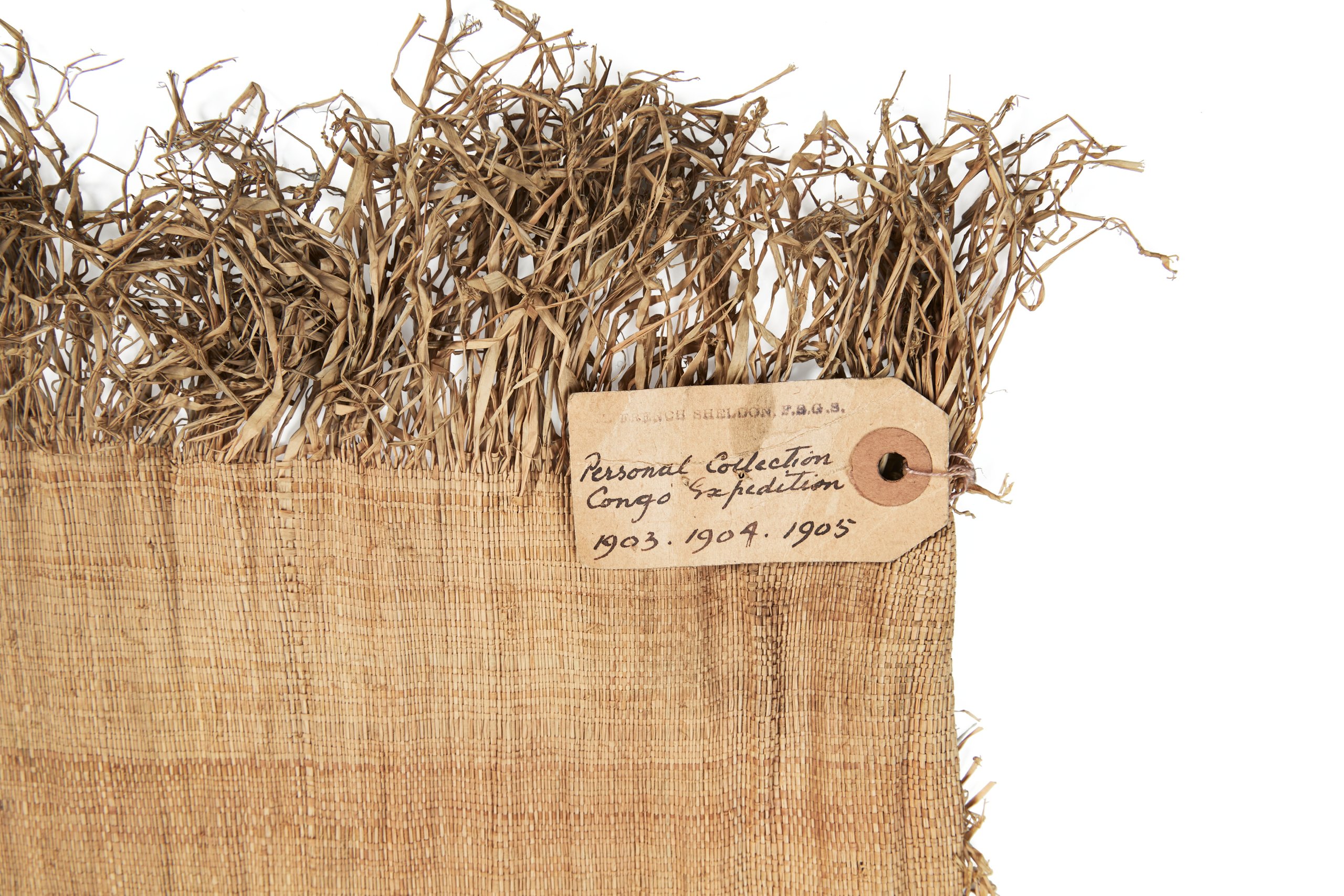

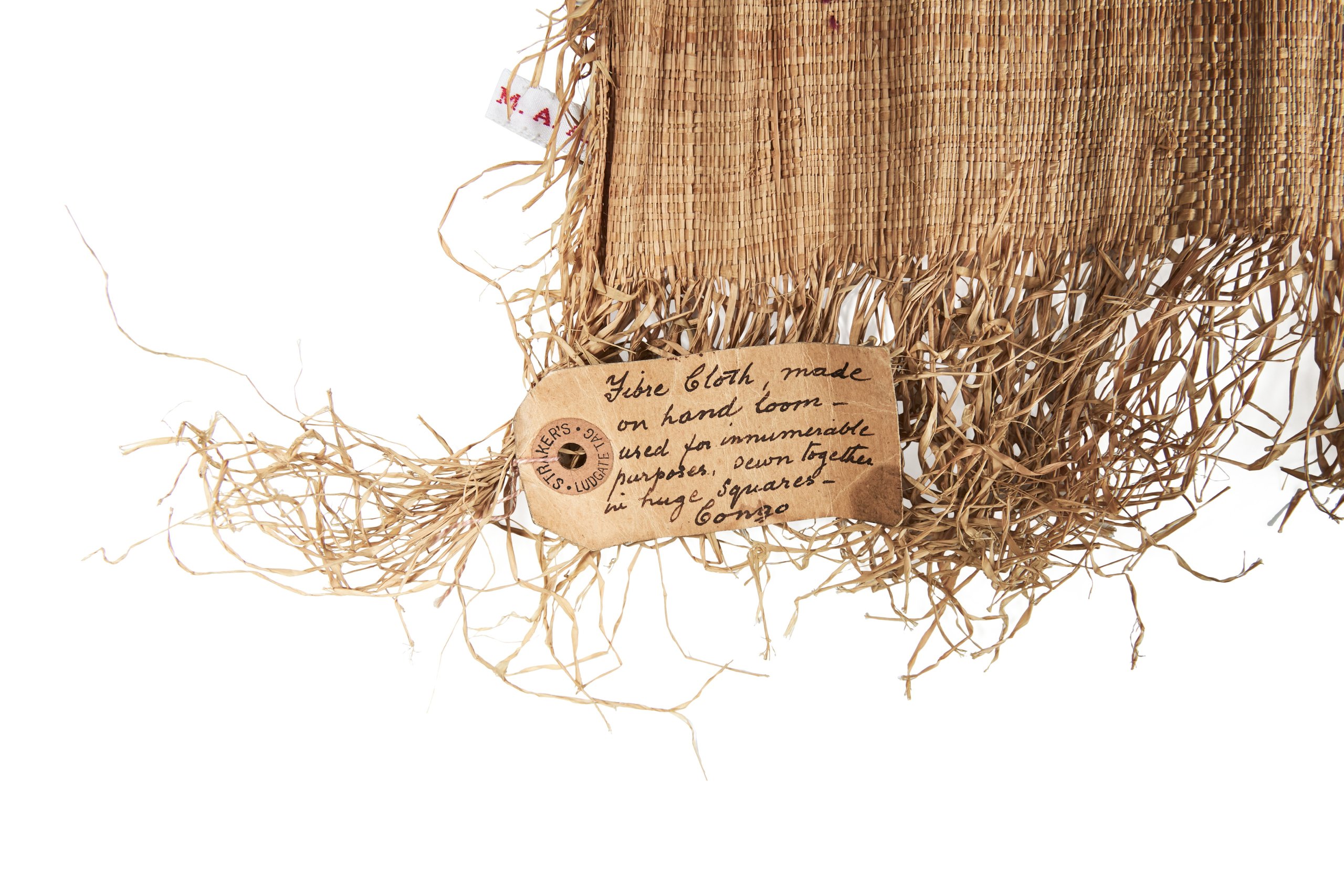

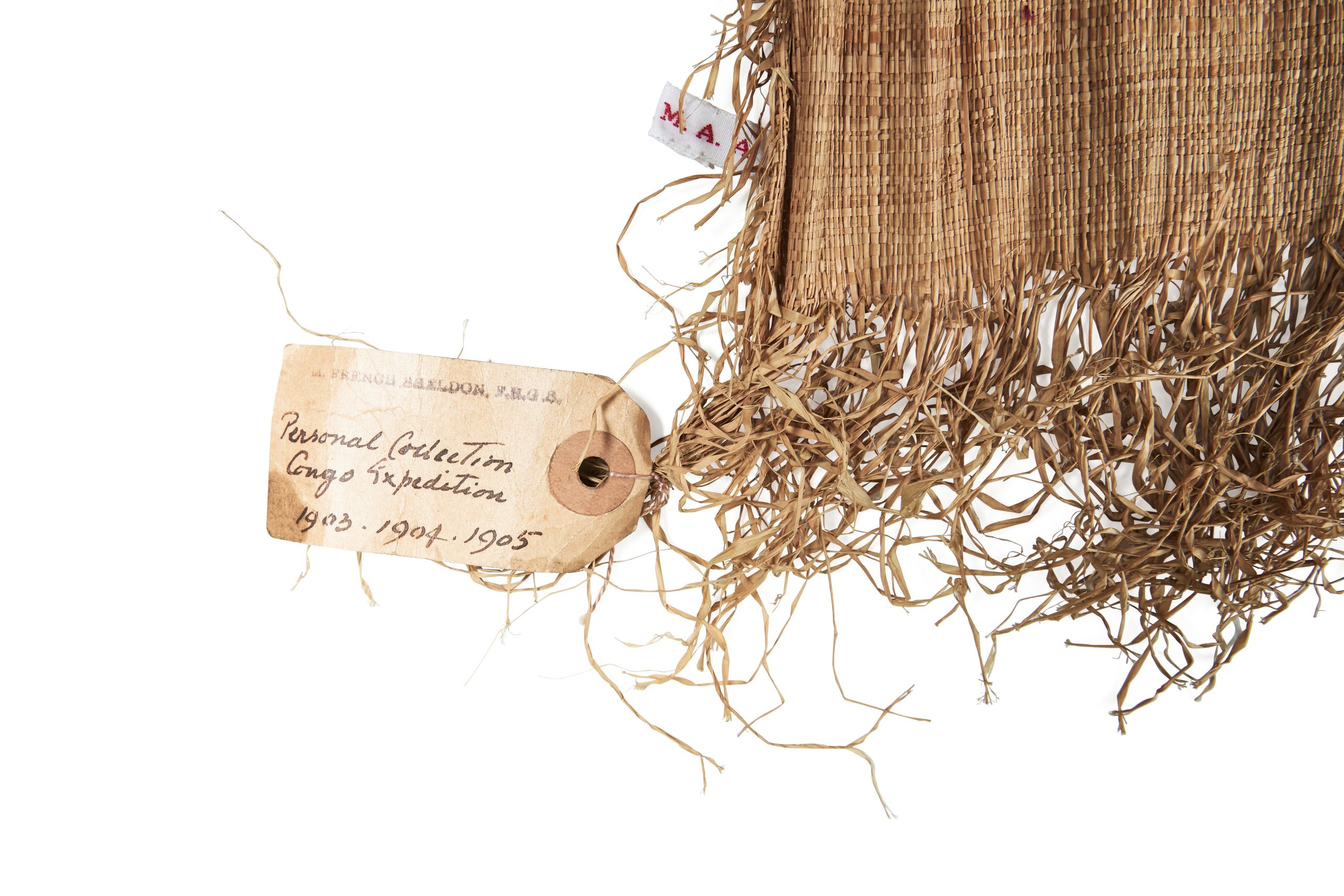

Four (4) rectangular pieces of plain weave cloth of raffia fibre, used as currency. Long sides have short fringes, ends have long fringes. Three are decorated with strips of narrow red, yellow and black ribbon, machined in place. Three have tie-on labels, which read; "M. French-Sheldon F.R.G.S. / Personal Collection / Congo Expedition / 1903. 1904. 1905" And on the reverse "Fibre cloth made / on hand loom - / used for innumerable / purposes, sewn together / in huge squares / Congo". Note. F.R.G.S stands for 'Fellow Royal Geographical Society' The fourth cloth has not been decorated with ribbon, and has been left plain. (Rebecca Fisher)

PRODUCTION

Notes

These four raffia currency mats were collected during the Mary (or May) French-Sheldon expedition to the Belgian Congo (now Zaire), 1903-1905. They were made in the Kuba region of Zaire, by unidentified Bakuba people (or person) of Kuba, between 1880 and 1905. In Kuba, creating textiles, such as raffia cloths, are a collaborative process. Men cultivate and weave the raffia, men and women decorate the cloths (although as will be seen some decoration was exclusively carried out by women), and both sew the cloths into garments. These four currency mats are made from raffia, which grows in wetland areas. Raffia palm trees (Raphia ruffia) grow most prolifically in West Africa and Central Africa. This textile was produced in Zaire, in Central Africa. Raffia cloths have traditionally been produced in Zaire, although the production of raffia cloth has decreased since European cotton cloths were brought into Africa. To produce this cloth, the fibre was removed from young raffia leaves (only young leaves are used in this process). This was achieved by cutting the leaves, and then leaving them in the shade while enough leaves are collected. A sharp knife was then used to cut partially through the base of the leaves, so as not to cut the membrane, and the outer leaves were removed. The membrane was clear when removed, and only looked like yellow grass when it had dried out (hanks were laid in the sun to dry for approximately half a day, and turned regularly to avoid twisting). In preparation for weaving, the strands of raffia were split in half with fingers or, as is the case in some areas of Zaire, such as Kuba, with a fine comb. As was usual in Zaire, the strands would have then been arranged for weaving on the loom. These textiles were woven by a male (in Zaire all weaving was and still is carried out by men), on a single-heddle loom. The process of weaving raffia on this loom is different to the weaving of threads, which are tied to the loom on a continuous warp. When weaving raffia, the warp threads are tied to the top and bottom of the loom, thus making it a non-continuous warp. This can be done easily by slipping the raffia hanks onto two batons, which are then attached to the loom. The majority of raffia weaving is produced in the same way, creating a naturally coloured plain weave, with hemmed edges. Raffia cloths are usually relatively small in size, largely due to the length of the raffia fibres. The average cloth is this usually approximately three or four feet squared. Cloth has been used throughout Africa as a form of currency for centuries. As discussed by the Smithsonian Institution; "In Africa, where few extensive nation-states existed, commerce among various societies depended on commonly held values that spanned great geographical distances and a broad diversity of activities. Societies assigned worth to objects that were relevant to their own circumstances: objects that were rare enough to be valued yet plentiful enough to be widely traded. Daily monetary transactions were conducted with cowrie shells, aggrey (glass) beads, woven cloth strips, and raffia mats" (The Artistry of African Currency- National Museum of African Art). The "bamboo" or wine palm (rafia vinifera or ntombe) is most commonly used for the construction of raffia currency. The simplest piece of cloth used as currency is the libongo (or Mbongo). These were usually woven with a simple plain weave, the size of a large handkerchief, and could be sewn together to items on clothing, large cloths, etc. Currency was exchanged in Africa during significant lifetime events, such as births, becoming an adult, marriages and deaths, or simply as a peace offering. The value of the currency was based on the quality of the mats. Raffia currency was also used at markets to purchase food and other essential items, sewn together to make clothing, bags and floor and bed covers, and were also saved for future expenses. (Rebecca Fisher)

HISTORY

Notes

The raffia loom originated in the Congo area. Weaving with raffia has traditionally been used in numerous areas throughout Africa, and plays an important traditional role in many aspects of life, including births, deaths and marriages. These four raffia currency mats are part of a collection of 32 objects donated by Mrs A. Marcovitch (nee Goninan) to the Powerhouse Museum in 1987. The objects donated by Mrs Marcovitch come from Yugoslavia, India, Africa and Samoa. The six objects from Africa were collected by May (or Mary) French-Sheldon during her Congo Expedition of 1903-1905. Mary French-Sheldon (1847-1936), more commonly known as May, was American born, and lived in London with her wealthy husband. She was a well travelled woman, but had never been to Africa. In 1891, at the age of 43, French-Sheldon went on a self-funded three month trek through the coast of East Africa, to the base of Mount Kilimanjaro, and back again. She claimed the title of "first woman explorer of Africa", although there are records of women travelling through Africa prior to French-Sheldon. However, she claimed the title because she was the believed herself to be the first woman to travel through Africa without a husband or European travel companion. French-Sheldon was by no means alone on her expedition, having 150 African porters with her on the journey. She also had considerable luxuries on this journey. She travelled with an elaborate court dress, of white silk and satin, with silver trim, glass and paste jewels, along with a tiara, waist-length platinum blond wig, leather whip, hip pistols and a ceremonial sword. May wore this ensemble to meetings with important African men, including the sultan. This dress was from the well known House of Worth, and she often called herself, and became known as the "White Queen". For the times when she wasn't walking, French-Sheldon was carried by her porters in a comfortable palanquin, complete with silk cushions. She also had her complete china tea service with her during her travels. May French-Sheldon explored Africa at a time when men and women had rigidly defined roles, and the world was male dominated. As discussed by Boisseau, "French-Sheldon sought acclaim as an African explorer in an era when this seemed the epitome of adventurous masculine pursuits (Boisseau, Sultan to Sultan, p. 3). During the Victorian era, terms like "adventuress" and "exploratress" were viewed as "unusual novelties" (Boisseau, White Queen, p.201), and travelling without a chaperone was viewed as unthinkable and dangerous. French-Sheldon, however, wanted to be recognised equally alongside the great male explorers, who had returned from Africa, and had become influential because of their knowledge gained during their explorations. As described by Boisseau, she had a "desire for glory" (Boisseau, White Queen, p.107). Her desire to be widely known is evident from a passage she wrote in Sultan to Sultan; "Unwilling to travel among these natives without leaving some evidence of my presence, I had taken the precaution to have several thousand rings, on which were engraved my name, and to every native with whom I personally came into contact in the course of time I presented one of these souvenirs" (Sultan to Sultan, p. 123) She even referred to herself as "Bebe Bwana", which in Swahili means "Woman Man". Thus, she displayed both womanly and manly characteristics, and is considered to be one of the early feminists. French-Sheldon became a very popular public figure after her return in 1891, portrayed in the media as a successful explorer. In 1892, she published her book Sultan to Sultan: Adventures among the Masai and other Tribes of East Africa (by M. French-Sheldon, "Bebe Bwana"). As described in the Journalist during this time; "Mrs. French-Sheldon, the distinguished author and traveller, delivered one of the most vivid and entertaining lectures heard in the Metropolis for a long time. She gave a telling description of her expedition, and a lurid account of the manners and customs of the people. Mrs. Sheldon is of distinguished personality, far-seeing insight and magnetic presence. The interest she has awakened by her courageous explorations and brainy lectures is almost unprecedented ('Journalist', New York). By 1895, French-Sheldon's husband had died, leaving her financially unable to support her further hopes for travel. Her popularity had also subsided. In 1903, May was hired to act as an undercover spy in Congo by William E. Stead, co founder of the Congo Reform Association. This fourteen-month trip, unlike her previous expedition, was "shrouded in secrecy" (Boisseau, White Queen, p.108), and it was during this trip to Africa that this cloth was collected by French-Sheldon. As described by Boisseau, her task was to gain information on the; "conditions in the Congo Free State that would damage the reputation of King Leopold II of Belgium and help orchestrate the release of his military and economic grip on the region. However, unbeknownst to Stead and Morel, French-Sheldon's sympathies lay with the beleaguered Belgian King and her actions in the Free State and in Britain upon her return seem to have been those of a double agent (Boisseau, White Queen, p.11). When she returned to Britain, controversy was raised by her reports, as they were "at odds with other British voices on Africa…" (Boisseau, White Queen, p.108). After this time, in 1905-1907, French-Sheldon tried to establish a rubber plantation and colonisation company in Liberia, from knowledge she gained whilst in the Congo. Her company, the Americo-Liberian Industrial Company, failed. After her return to England, French-Sheldon once again became a very popular figure, having a particularly "profound effect on her young female audience in the 1920s" Boisseau, White Queen, p.182) with her public speaking. French-Sheldon, described in the St. Thomas newspaper as "one of the grandest women of the age", left a lasting impression on many during her lifetime and after. As encapsulated by the newspaper, The Carmel Pine Cone; "Hardly can we look now at the map of Africa without picturing [Madame French-Sheldon] that small dauntless figure, revolver in her belt, marching at the head of her mile-long line of natives across that land of mystery" (Carmel Pine Cone, February 16, 1924). (Rebecca Fisher)

SOURCE

Credit Line

Gift of A Marcovitch, 1989

Acquisition Date

23 August 1989

Copyright for the above image is held by the Powerhouse and may be subject to third-party copyright restrictions. Please submit an Image Licensing Enquiry for information regarding reproduction, copyright and fees. Text is released under Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivative licence.

Image Licensing Enquiry

Object Enquiry